Loans

Lump-sum repayment, explicit interest

1/1/X1, XYZ borrowed 100,000 from a bank for five years agreeing to pay 7.5% interest annually.

As it was stated in the contract, the explicit interest rate was 7.5%.

Loan contracts generally specify interest rates. As they are explicitly stated, they are commonly known as explicit or stated interest rates. They may also be referred to as quoted, coupon or nominal rates.

In contrast, implicit interest rates, also known as implied, real or effective rates, are not stated but rather implied by the cash flows associated with the contract.

The terms implicit and effective can be used interchangeably.

Specifically, US GAAP uses implicit interest to define effective interest, making the two synonyms.

ASC Master Glossary (edited): The rate of return implicit in the financial asset, that is, the contractual interest rate adjusted for any net deferred fees or costs, premium, or discount existing at the origination or acquisition of the financial asset...

Interestingly, the definition (as updated by ASU 2016-13) addresses the issue by referring to a financial asset.

In contrast, the previous definition referred to a loan: The rate of return implicit in the loan, that is, the contractual interest rate adjusted for any net deferred loan fees or costs, premium, or discount existing at the origination or acquisition of the loan.

From a practical perspective however, it make no difference as effective interest is determined the same way in both situations: by evaluating cash flow.

Interestingly, besides defining the term, the IFRS 9 definition also explains how to calculate effective interest.

IFRS 9 Defined terms (edited): ... When calculating the effective interest rate, an entity shall estimate the expected cash flows by considering all the contractual terms of the financial instrument (for example, prepayment, extension, call and similar options) but shall not consider the expected credit losses. The calculation includes all fees and points paid or received between parties to the contract that are an integral part of the effective interest rate ..., transaction costs, and all other premiums or discounts. There is a presumption that the cash flows and the expected life of a group of similar financial instruments can be estimated reliably. However, in those rare cases when it is not possible to reliably estimate the cash flows or the expected life of a financial instrument (or group of financial instruments), the entity shall use the contractual cash flows over the full contractual term of the financial instrument (or group of financial instruments).

Presumably because it considers it obvious, the ASC does not go into such detail. Thus, as they more or less describe how it is done in practice anyway, the instructions in IFRS 9 can be considered in a US GAAP context, especially since this is suggested in ASC 105-10-05-3.d.

While IFRS does not incorporate implicit into its definition, the definition itself yields a comparable result.

IFRS 9 Defined terms (edited): The rate that exactly discounts estimated future cash payments or receipts through the expected life of the financial asset or financial liability to the gross carrying amount of a financial asset or to the amortised cost of a financial liability...

In addition to defining effective interest, IFRS 9 Defined terms explains how it should be calculated.

Defined terms (edited): ... When calculating the effective interest rate, an entity shall estimate the expected cash flows by considering all the contractual terms of the financial instrument (for example, prepayment, extension, call and similar options) but shall not consider the expected credit losses. The calculation includes all fees and points paid or received between parties to the contract that are an integral part of the effective interest rate ..., transaction costs, and all other premiums or discounts. There is a presumption that the cash flows and the expected life of a group of similar financial instruments can be estimated reliably. However, in those rare cases when it is not possible to reliably estimate the cash flows or the expected life of a financial instrument (or group of financial instruments), the entity shall use the contractual cash flows over the full contractual term of the financial instrument (or group of financial instruments).

As the ASC does not provide guidance on how to calculate effective interest, the above approach, as outlined in ASC 105-10-05-3.d, is applicable in a US GAAP context as well.

If the explicit rate differs from the implicit rate, the transaction is measured using the implicit rate. However, if they are the same as in this illustration, no adjustment is needed.

In this illustration, the implicit rate is obvious: 7.5% = 7,500 ÷ 100,000.

In less obvious situations, the implicit rate would need to be determined.

For example, if XYZ had sold a note with a nominal value of 100,000 and 7.5% coupon for 98,000, the explicit interest rate would still be 7.5%, but the implicit rate would not. Obviously, one cannot simply calculate 7.65% = 7,500 ÷ 98,000. Instead, the implicit rate needs to be determined.

The simplest way is Excel's =IRR (or =XIRR) function:

As it allows exact dates to be entered, =XIRR yields a more accurate result.

P |

Date |

|

Cash flow |

A |

B |

|

C |

0 |

1/1/X0 |

|

(98,000) |

1 |

1/1/X1 |

|

7,500 |

2 |

1/1/X2 |

|

7,500 |

3 |

1/1/X3 |

|

7,500 |

4 |

1/1/X4 |

|

7,500 |

5 |

1/1/X5 |

|

107,500 |

|

|

|

7.99671679735184%=XIRR(B0:B5,C0:C5,0.1) |

In some situations, this is too accurate.

But, the result can always be rounded 8%=ROUND(XIRR(B0:B5,C0:C5,0.1),0).

P |

|

|

Cash flow |

A |

|

|

B |

0 |

|

|

(98,000) |

1 |

|

|

7,500 |

2 |

|

|

7,500 |

3 |

|

|

7,500 |

4 |

|

|

7,500 |

5 |

|

|

107,500 |

|

|

|

8%=IRR(B0:B5) |

It can also be calculated by trial and error using a present value schedule:

P |

Payment |

Discount rate |

Present value |

A |

B |

C |

D = B ÷ (1 + C)A |

1 |

7,500 |

8% |

6,944 |

2 |

7,500 |

8% |

6,430 |

3 |

7,500 |

8% |

5,954 |

4 |

7,500 |

8% |

5,513 |

5 |

107,500 |

8% |

73,163 |

|

|

|

98,000 |

|

|

|

|

1/1/X1 | 1.1.X1 |

|

|

|

Cash |

100,000 |

|

|

|

Loan |

|

|

With a term loan, where the principal is repaid as a lump sum, present value equals nominal value.

This fact can easily be demonstrated by discounting the loan's cash flow to present value:

P |

Payment |

Discount rate |

Present value |

A |

B |

C |

D = B ÷ (1 + C)A |

1 |

7,500 |

7.5% |

6,977 |

2 |

7,500 |

7.5% |

6,490 |

3 |

7,500 |

7.5% |

6,037 |

4 |

7,500 |

7.5% |

5,616 |

5 |

107,500 |

7.5% |

74,880 |

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|

|

|

Note: as outlined in IFRS 9.5.1.1, all liabilities are initially measured at fair value.

IFRS 9.5.1.1 states (edited): ... an entity shall measure a financial asset or financial liability at its fair value plus or minus, in the case of a financial asset or financial liability not at fair value through profit or loss, transaction costs...

While ASC 405-10, 470-10 does not provide any explicit guidance on the initial measurement of financial liabilities, ASC 835-30 does provide guidance on imputed interest which leads to a comparable result.

If the borrower and lender are market participants and have not entered into a supplemental or unwritten agreement, present value will reflect fair value.

Historically, arm’s length was the criterion for evaluating transactions and determining value.

Although the term appears in some (older) guidance, neither IFRS nor US GAAP have ever defined arm's length.

However, a good working definition is a price in an exchange between parties that are:

- unrelated

- fully informed, and

- acting voluntarily.

Also see one of the better summaries: link law.cornell.edu.

Note: the concept of arm's length features prominently in OECD, particularly transfer pricing, guidance. However, as the OECD’s purpose is to further cooperation between governments in developing common taxation policies, its influence on IFRS and US GAAP is derivative. For this reason, most accountants do not need to consider this guidance, which is fortunate since, unlike the IASB and FASB which make their guidance, in the public interest, freely available on line, the OECD hides its behind a paywall.

Currently, the criteria are orderly transactions between market participants.

Before IFRS 13 | ASC 820, arm's length transactions were the way to objectively determine value.

While orderly transactions between market participants have supplanted arm's length, remnants can still be found in some older guidance (i.e. IAS 24.23 or IAS 36.52 | ASC 460-10-30-2 or ASC 850-10-50-5).

Since IFRS 13 | ASC 820, transactions must be orderly instead.

IFRS 13 | ASC 820 define orderly: A transaction that assumes exposure to the market for a period before the measurement date to allow for marketing activities that are usual and customary for transactions involving such assets or liabilities; it is not a forced transaction (for example, a forced liquidation or distress sale).

In addition to being orderly, IFRS 13 | ASC 820 also requires the transactions to be between market participants, or buyers/sellers that are:

- independent

- knowledgeable

- willing and

- able

IFRS 13 | ASC 820 definition: Buyers and sellers in the principal (or most advantageous) market for the asset or liability that have all of the following characteristics:

- They are independent of each other, that is, they are not related parties, although the price in a related-party transaction may be used as an input to a fair value measurement if the reporting entity has evidence that the transaction was entered into at market terms

- They are knowledgeable, having a reasonable understanding about the asset or liability and the transaction using all available information, including information that might be obtained through due diligence efforts that are usual and customary

- They are able to enter into a transaction for the asset or liability

- They are willing to enter into a transaction for the asset or liability, that is, they are motivated but not forced or otherwise compelled to do so.

A stated interest rate could be unreasonable for various reasons.

The most common, assuming they are unrelated, the debtor and creditor have entered into a side agreement.

As outlined in ASC 835-30-25-6, if the interest associated with a liability is influenced by a side agreement, written or unwritten, it is adjusted to reflect the effect of that agreement.

ASC 835-30-25-6 (edited, emphasis added) states: A note issued solely for cash equal to its face amount is presumed to earn the stated rate of interest. However, in some cases the parties may also exchange unstated (or stated) rights or privileges, which are given accounting recognition by establishing a note discount or premium account. In such instances, the effective interest rate differs from the stated rate...

While ASC 835-30-25-4 to 11 discusses notes, by analogy the guidance applies to any (financial) liability.

As the name suggests, an unstated right or privilege is, well, unstated.

But, while the guidance talks about the chicken, the accountant is more interested in the egg.

While paragraph ASC 835-30-25-6 correctly points out that the unstated right or privilege is the cause of the unreasonable rate, since the unstated right of privilege is unstated, the accountant will only see the result: the unreasonable rate.

In other words, when a rate is unreasonable, the right or privilege that laid it needs to be tracked down.

To expand on this silly metaphor, since whomever hid the chicken may have gone out of their way to make sure it stays hidden, just like the T-X and Sandor Clegane's love child, a good accountant will never stop until they get their chicken.

On a serious note, finding, recognizing and measuring unstated right and privileges is always crucial, but especially so if the accountant has a Sarbanes-Oxley or similar obligation.

While IFRS 9 does not discuss "unstated rights or privileges," the guidance it does provide has the same effect.

IFRS 9.5.1.1 specifies that financial liabilities are measured at fair value (plus transaction costs in some situations).

IFRS 9.B5.1.1 elaborates on this general guidance by stating (edited): ... For example, the fair value of a long-term loan or receivable that carries no interest can be measured as the present value of all future cash receipts discounted using the prevailing market rate(s) of interest for a similar instrument...

Obviously, if a liability carries no interest, there has to be a reason. If the parties are unrelated, informed and acting voluntarily, the only possible reason could be an additional right or privilege.

By implication, the same logic applies if the stated (nominal or explicit) rate is not reasonable. If it is too low, the creditor has an additional right or privilege. If it is too high, the right or privilege belongs to the debtor.

Even if the borrower and lender are not market participants or have entered into a supplemental or unwritten agreement, present value will still reflect fair value. The only difference, present value will be determined using an imputed interest rate (below).

|

|

||

Interest |

|

||

|

Cash |

|

7,500 |

To simplify its accounting (and reduce liabilities), XYZ paid the 31st. Otherwise, it would have recognized:

12/31/X1 | 31.12.X1 |

|

|

|

Interest |

7,500 |

|

|

|

Accrued interest |

|

7,500 |

1/1/X2 | 1.1.X2 |

|

|

|

Accrued interest |

7,500 |

|

|

|

Cash |

|

7,500 |

If explicit interest is reasonable, it is recognized without adjustment.

If explicit interest is not reasonable, imputed interest is recognized instead.

As outlined in ASC 835-30, an interest rate must be reasonable, in that it must reflect an established exchange price for the liability. If not, a reasonable interest rate, one that does reflect this price, is imputed.

ASC 835-20 defines imputed interest rate: the interest rate that results from a process of approximation (or imputation) required when the present value of a note must be estimated because an established exchange price is not determinable and the note has no ready market.

Although the guidance specifically discusses notes, by analogy it applies to any financial liability.

ASC 835-20-25-4 to 11 go on to discuss various scenarios where imputation is necessary, such as when the agreement includes an unstated right or privilege, or the liability is incurred in exchange for a good or service.

Finally, ASC 835-20-25-12 and 13 suggest the methodology that should be used, but do not preclude different methodology if it can yield a more accurate result.

While "imputation" in only discussed in the ASC, IFRS 9 does provide guidance with a comparable result.

While IFRS 9 does not specifically mention imputation, IFRS 9.5.1.1 does require liabilities to be measured at fair value. Including its supplemental guidance, the standard yields results comparable to US GAAP.

For example, IFRS 9.B5.1.1 (edited, emphasis added) states: The fair value of a financial instrument at initial recognition is normally the transaction price... However, if part of the consideration given or received is for something other than the financial instrument, an entity shall measure the fair value of the financial instrument. For example, the fair value of a long-term loan or receivable that carries no interest can be measured as the present value of all future cash receipts discounted using the prevailing market rate...

In comparison ASC 835-30-25-6 (edited) states: A note issued solely for cash equal to its face amount is presumed to earn the stated rate of interest. However, in some cases the parties may also exchange unstated (or stated) rights or privileges, which are given accounting recognition by establishing a note discount or premium account. In such instances, the effective interest rate differs from the stated rate. For example, an entity may lend a supplier cash that is to be repaid five years hence with no stated interest. Such a non-interest-bearing loan may be partial consideration under a purchase contract for supplier products at lower than the prevailing market prices. In this circumstance, the difference between the present value of the receivable and the cash loaned to the supplier is appropriately regarded as an addition to the cost of products purchased during the contract term...

Although IFRS 9.B5.1.1 refers to both fair value and the prevailing market rate, while ASC 835-30-25-6 only to prevailing market prices, both require interest to reflect those prevailing market rates | prices. Whether the process is called imputation or something else is just semantics.

As XYZ and the bank transacted as market participants with no side agreement, 7.5% was reasonable.

Historically, arm’s length was the criterion for evaluating transactions and determining value.

Although the term appears in some (older) guidance, neither IFRS nor US GAAP have ever defined arm's length.

However, a good working definition is a price in an exchange between parties that are:

- unrelated

- fully informed, and

- acting voluntarily.

Also see one of the better summaries: link law.cornell.edu.

Note: the concept of arm's length features prominently in OECD, particularly transfer pricing, guidance. However, as the OECD’s purpose is to further cooperation between governments in developing common taxation policies, its influence on IFRS and US GAAP is derivative. For this reason, most accountants do not need to consider this guidance, which is fortunate since, unlike the IASB and FASB which make their guidance, in the public interest, freely available on line, the OECD hides its behind a paywall.

Currently, the criteria are orderly transactions between market participants.

Before IFRS 13 | ASC 820, arm's length transactions were the way to objectively determine value.

While orderly transactions between market participants have supplanted arm's length, remnants can still be found in some older guidance (i.e. IAS 24.23 or IAS 36.52 | ASC 460-10-30-2 or ASC 850-10-50-5).

Since IFRS 13 | ASC 820, transactions must be orderly instead.

IFRS 13 | ASC 820 define orderly: A transaction that assumes exposure to the market for a period before the measurement date to allow for marketing activities that are usual and customary for transactions involving such assets or liabilities; it is not a forced transaction (for example, a forced liquidation or distress sale).

In addition to being orderly, IFRS 13 | ASC 820 also requires the transactions to be between market participants, or buyers/sellers that are:

- independent

- knowledgeable

- willing and

- able

IFRS 13 | ASC 820 definition: Buyers and sellers in the principal (or most advantageous) market for the asset or liability that have all of the following characteristics:

- They are independent of each other, that is, they are not related parties, although the price in a related-party transaction may be used as an input to a fair value measurement if the reporting entity has evidence that the transaction was entered into at market terms

- They are knowledgeable, having a reasonable understanding about the asset or liability and the transaction using all available information, including information that might be obtained through due diligence efforts that are usual and customary

- They are able to enter into a transaction for the asset or liability

- They are willing to enter into a transaction for the asset or liability, that is, they are motivated but not forced or otherwise compelled to do so.

A stated interest rate could be unreasonable for various reasons.

The most common, assuming they are unrelated, the debtor and creditor have entered into a side agreement.

As outlined in ASC 835-30-25-6, if the interest associated with a liability is influenced by a side agreement, written or unwritten, it is adjusted to reflect the effect of that agreement.

ASC 835-30-25-6 (edited, emphasis added) states: A note issued solely for cash equal to its face amount is presumed to earn the stated rate of interest. However, in some cases the parties may also exchange unstated (or stated) rights or privileges, which are given accounting recognition by establishing a note discount or premium account. In such instances, the effective interest rate differs from the stated rate...

While ASC 835-30-25-4 to 11 discusses notes, by analogy the guidance applies to any (financial) liability.

As the name suggests, an unstated right or privilege is, well, unstated.

But, while the guidance talks about the chicken, the accountant is more interested in the egg.

While paragraph ASC 835-30-25-6 correctly points out that the unstated right or privilege is the cause of the unreasonable rate, since the unstated right of privilege is unstated, the accountant will only see the result: the unreasonable rate.

In other words, when a rate is unreasonable, the right or privilege that laid it needs to be tracked down.

To expand on this silly metaphor, since whomever hid the chicken may have gone out of their way to make sure it stays hidden, just like the T-X and Sandor Clegane's love child, a good accountant will never stop until they get their chicken.

On a serious note, finding, recognizing and measuring unstated right and privileges is always crucial, but especially so if the accountant has a Sarbanes-Oxley or similar obligation.

While IFRS 9 does not discuss "unstated rights or privileges," the guidance it does provide has the same effect.

IFRS 9.5.1.1 specifies that financial liabilities are measured at fair value (plus transaction costs in some situations).

IFRS 9.B5.1.1 elaborates on this general guidance by stating (edited): ... For example, the fair value of a long-term loan or receivable that carries no interest can be measured as the present value of all future cash receipts discounted using the prevailing market rate(s) of interest for a similar instrument...

Obviously, if a liability carries no interest, there has to be a reason. If the parties are unrelated, informed and acting voluntarily, the only possible reason could be an additional right or privilege.

By implication, the same logic applies if the stated (nominal or explicit) rate is not reasonable. If it is too low, the creditor has an additional right or privilege. If it is too high, the right or privilege belongs to the debtor.

As a general rule:

- Commercial emprises and their banks are independent (unrelated).

- Unless the enterprise has committed bank fraud, it and its bank are knowledgeable (fully informed).

- Ability is a non-issue.

- It is hard to imagine a scenario where an enterprise or its bank would act unwillingly.

IFRS 13 | ASC 820 deals with fair value which is the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability. Consequently, the guidance needs to consider the future. One way future value can be determined is a future exchange. In this situation, the ability of the parties to act in the future needs to be evaluated. If the transaction has already occurred, the parties were obviously able. The only reason it appears in this list, it is part of the definition of market participants (above), so cannot be omitted.

Finally, while conceivable, in jurisdictions with adequate regulation, banks do not enter into unwritten agreements with their clients. So, as a general rule, whatever interest a bank and its client agree to is, a priori, reasonable.

Note: although required by IFRS 9.4.2.1 | ASC 835-30-55-2, XYZ did not apply the effective interest method.

ASC 835-30-55-2 specifically requires financial liabilities to be measured using the [effective] interest method.

While it does not explicitly express this requirement, IFRS 9.4.2.1 does require amortised cost and effective interest is part of the definition of amortised cost.

This implies the effective interest method must always be used for IFRS and US GAAP purposes.

However, if the principal received and re-paid are equal, and the stated rate is reasonable, explicit interest equals effective interest, so simply recognizing this interest as expense as it is paid achieves the required result.

12/31/X5 | 31.12.X5 |

|

|

|

Interest |

7,500 |

|

|

Loan |

100,000 |

|

|

|

Cash |

|

107,500 |

Same facts except XYZ recognized interest each quarter so it could report it in its interim reports.

12/31/X1 | 31.12.X1 |

|

|

|

Interest |

|

||

|

Accrued interest |

|

1,875 |

As interest is paid annually, there is no need to apply an interim interest rate. The annual expense can simply be accrued to each interim period.

12/31/X5 | 31.12.X5 |

|

|

|

Loan |

100,000 |

|

|

Interest |

7,500 |

|

|

Accrued interest |

5,625 |

|

|

|

Cash |

|

107,500 |

Same facts except XYZ paid a 2% origination fee.

1/1/X1 | 1.1.X1 |

|

|

|

Cash |

98,000 |

|

|

|

Loan |

|

|

As outlined in IFRS 9.5.1.1 | ASC 835-30-45-1A, transaction costs are deducted from the liability.

Unlike ASC 835-30-45, IFRS 9.B5.4.1 to 4 also go into some detail about costs reflected (IFRS 9.B5.4.2) / not reflected (IFRS 9.B5.4.3) in effective interest (deducted / not deducted from the liability). However, this additional guidance is not relevant to the situation being illustrated.

While not in line with the letter of the guidance, using an adjustment account leads to prettier accounting.

Cash |

98,000 |

|

|

Deferred origination fee |

2,000 |

|

|

|

Loan |

|

100,000 |

Interest |

7,841 |

|

|

|

Deferred origination fee |

|

341 |

|

Loan |

|

7,500 |

- Etc. - |

|

|

|

Loan |

107,500 |

|

|

|

Cash |

|

107,500 |

|

|

|

||

|

Interest |

7,841 |

|

|

| Loan | |||

|

|

Cash |

|

7,500 |

Technically, interest increases the liability while the payment decreases it, which is apparent if the payment is made in the following period:

12/31/X1 | 31.12.X1 |

|

|

|

Interest |

7,841 |

|

|

|

Loan |

|

7,841 |

1/1/X2 | 1.1.X2 |

|

|

|

Loan |

7,500 |

|

|

|

Cash |

|

7,500 |

As the loan's face value ≠ its nominal value, the difference was amortized using the implicit rate.

The simplest way to calculate an implicit rate is Excel's =IRR or =XIRR function.

As it allows exact dates to be entered, =XIRR yields a more accurate result.

P |

Date |

|

Cash flow |

A |

B |

|

C |

0 |

1/1/X0 |

|

(98,000) |

1 |

1/1/X1 |

|

7,500 |

2 |

1/1/X2 |

|

7,500 |

3 |

1/1/X3 |

|

7,500 |

4 |

1/1/X4 |

|

7,500 |

5 |

1/1/X5 |

|

107,500 |

|

|

|

7.99671679735184%=XIRR(B0:B5,C0:C5,0.1) |

P |

|

|

Cash flow |

A |

|

|

B |

0 |

|

|

(98,000) |

1 |

|

|

7,500 |

2 |

|

|

7,500 |

3 |

|

|

7,500 |

4 |

|

|

7,500 |

5 |

|

|

107,500 |

|

|

|

8%=IRR(B0:B5) |

It can also be calculated by trial and error using a present value schedule:

P |

Payment |

Discount rate |

Present value |

A |

B |

C |

D = B ÷ (1 + C)A |

1 |

7,500 |

8% |

6,944 |

2 |

7,500 |

8% |

6,430 |

3 |

7,500 |

8% |

5,954 |

4 |

7,500 |

8% |

5,513 |

5 |

107,500 |

8% |

73,163 |

|

|

|

98,000 |

|

|

|

|

P |

Loan balance |

Interest rate |

Interest expense |

Cash flow |

Amortization |

A |

B = B(B+1) - F |

C |

D = B x C |

E |

F = E - D |

1 |

98,000 |

8% |

7,841 |

7,500 |

(341) |

2 |

98,341 |

8% |

7,868 |

7,500 |

(368) |

3 |

98,709 |

8% |

7,989 |

7,500 |

(398) |

4 |

99,107 |

8% |

7,929 |

7,500 |

(429) |

5 |

99,536 |

8% |

7,964 |

107,500 |

99,536 |

|

|

|

|

|

98,000 |

|

|||||

12/31/X5 | 31.12.X5 |

|

|

|

Interest |

7,964 |

|

|

Loan |

99,536 |

|

|

|

Cash |

|

107,500 |

Serial repayment, implicit interest

1/1/X1, XYZ borrowed 100,000 from a bank agreeing to re-pay the loan with five annual installments of 24,716.

As an explicit rate was not stated in the contract, XYZ calculated an implicit interest rate.

Loan contracts generally specify interest rates. As they are explicitly stated, they are commonly known as explicit or stated interest rates. They may also be referred to as quoted, coupon or nominal rates.

However, in this illustration, the agreement failed to specify an interest rate so an implicit (a.k.a. implied, real or effective) interest rate needed to be determined.

The terms implicit and effective can be used interchangeably.

Specifically, US GAAP uses implicit interest to define effective interest, making the two synonyms.

ASC Master Glossary (edited): The rate of return implicit in the financial asset, that is, the contractual interest rate adjusted for any net deferred fees or costs, premium, or discount existing at the origination or acquisition of the financial asset...

Interestingly, the definition (as updated by ASU 2016-13) addresses the issue by referring to a financial asset.

In contrast, the previous definition referred to a loan: The rate of return implicit in the loan, that is, the contractual interest rate adjusted for any net deferred loan fees or costs, premium, or discount existing at the origination or acquisition of the loan.

From a practical perspective however, it make no difference as effective interest is determined the same way in both situations: by evaluating cash flow.

Interestingly, besides defining the term, the IFRS 9 definition also explains how to calculate effective interest.

IFRS 9 Defined terms (edited): ... When calculating the effective interest rate, an entity shall estimate the expected cash flows by considering all the contractual terms of the financial instrument (for example, prepayment, extension, call and similar options) but shall not consider the expected credit losses. The calculation includes all fees and points paid or received between parties to the contract that are an integral part of the effective interest rate ..., transaction costs, and all other premiums or discounts. There is a presumption that the cash flows and the expected life of a group of similar financial instruments can be estimated reliably. However, in those rare cases when it is not possible to reliably estimate the cash flows or the expected life of a financial instrument (or group of financial instruments), the entity shall use the contractual cash flows over the full contractual term of the financial instrument (or group of financial instruments).

Presumably because it considers it obvious, the ASC does not go into such detail. Thus, as they more or less describe how it is done in practice anyway, the instructions in IFRS 9 can be considered in a US GAAP context, especially since this is suggested in ASC 105-10-05-3.d.

While IFRS does not incorporate implicit into its definition, the definition itself yields a comparable result.

IFRS 9 Defined terms (edited): The rate that exactly discounts estimated future cash payments or receipts through the expected life of the financial asset or financial liability to the gross carrying amount of a financial asset or to the amortised cost of a financial liability...

The payment implied a 7.5% interest rate.

The lender calculated the payment (in Excel syntax): 24716=ROUND(100000/((1-(1/(1+7.5%)^5))/7.5%), 0)

To calculate the implicit rate, XYZ evaluated the cash flow associated with the loan.

Interestingly, besides defining the term, the IFRS 9 definition also explains how to calculate effective interest.

IFRS 9 Defined terms (edited): ... When calculating the effective interest rate, an entity shall estimate the expected cash flows by considering all the contractual terms of the financial instrument (for example, prepayment, extension, call and similar options) but shall not consider the expected credit losses. The calculation includes all fees and points paid or received between parties to the contract that are an integral part of the effective interest rate ..., transaction costs, and all other premiums or discounts. There is a presumption that the cash flows and the expected life of a group of similar financial instruments can be estimated reliably. However, in those rare cases when it is not possible to reliably estimate the cash flows or the expected life of a financial instrument (or group of financial instruments), the entity shall use the contractual cash flows over the full contractual term of the financial instrument (or group of financial instruments).

Presumably because it considers it obvious, the ASC does not go into such detail. Thus, as they more or less describe how it is done in practice anyway, the instructions in IFRS 9 can be considered in a US GAAP context, especially since this is suggested in ASC 105-10-05-3.d.

The simplest way to do so (in Excel syntax): 7.5%=ROUND(RATE(5,-24716,100000,0,0), 3).

Although not as simple, =IRR or =XIRR also do the job.

As it allows exact dates to be entered, =XIRR yields a more accurate result.

P |

Date |

|

Cash flow |

A |

B |

|

C |

0 |

1/1/X0 |

|

(100,000) |

1 |

1/1/X1 |

|

24,716 |

2 |

1/1/X2 |

|

24,716 |

3 |

1/1/X3 |

|

24,716 |

4 |

1/1/X4 |

|

24,716 |

5 |

1/1/X5 |

|

24,716 |

|

|

|

7.49733656644821%=XIRR(B0:B5,C0:C5,0.1) |

In some situations, this is too accurate.

But, the result can always be rounded 7.5%=ROUND(XIRR(B0:B5,C0:C5,0.1),3).

P |

|

|

Cash flow |

A |

|

|

B |

0 |

|

|

(100,000) |

1 |

|

|

24,716 |

2 |

|

|

24,716 |

3 |

|

|

24,716 |

4 |

|

|

24,716 |

5 |

|

|

24,716 |

|

|

|

7.5%=IRR(B0:B5) |

The =IRR/=XIRR function is appropriate when, as in the previous illustration, the cash flows are not all equal. When they are, the =Rate function, since it does not require a schedule to be set up, is faster.

Another way is by trial and error using a present value schedule:

P |

Payment |

Discount rate |

Present value |

A |

B |

C |

D = B ÷ (1 + C)A |

1 |

24,716 |

7.5% |

22,992 |

2 |

24,716 |

7.5% |

21,388 |

3 |

24,716 |

7.5% |

19,896 |

4 |

24,716 |

7.5% |

18,508 |

5 |

24,716 |

7.5% |

17,216 |

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|

|

|

1/1/X1 | 1.1.X1 |

|

|

|

Cash |

100,000 |

|

|

|

Loan |

|

|

The present value of 5 x 24,716 discounted using a 7.5% (implicit) rate is 100,000.

In excel syntax: 100000=24716*((1-(1+7.5%)^-5)/7.5%) or using a PV schedule.

P |

Payment |

Discount rate |

Present value |

A |

B |

C |

D = B ÷ (1 + C)A |

1 |

24,716 |

7.5% |

22,992 |

2 |

24,716 |

7.5% |

21,388 |

3 |

24,716 |

7.5% |

19,896 |

4 |

24,716 |

7.5% |

18,508 |

5 |

24,716 |

7.5% |

17,216 |

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|

|

|

Note: the PV of 24716 is actually 99998=ROUND(24716*((1-(1+7.5%)^-5)/7.5%),0).

However, if the payment had been calculated to the 1/100th 24716.47=ROUND(100000/((1-(1/(1+7.5%)^5))/7.5%),2) as is common practice, PV would have been 99999.99=ROUND(24716.47*((1-(1+7.5%)^-5)/7.5%),2), which is close enough to 100,000 for illustration purposes.

Note: as outlined in IFRS 9.5.1.1, all liabilities are initially measured at fair value.

IFRS 9.5.1.1 states (edited): ... an entity shall measure a financial asset or financial liability at its fair value plus or minus, in the case of a financial asset or financial liability not at fair value through profit or loss, transaction costs...

While ASC 405-10, 470-10 does not provide any explicit guidance on the initial measurement of financial liabilities, ASC 835-30 does provide guidance on imputed interest which leads to a comparable result.

However, assuming the borrower and lender are market participants and have not entered into a supplemental or unwritten agreement, present value will reflect fair value.

Historically, arm’s length was the criterion for evaluating transactions and determining value.

Although the term appears in some (older) guidance, neither IFRS nor US GAAP have ever defined arm's length.

However, a good working definition is a price in an exchange between parties that are:

- unrelated

- fully informed, and

- acting voluntarily.

Also see one of the better summaries: link law.cornell.edu.

Note: the concept of arm's length features prominently in OECD, particularly transfer pricing, guidance. However, as the OECD’s purpose is to further cooperation between governments in developing common taxation policies, its influence on IFRS and US GAAP is derivative. For this reason, most accountants do not need to consider this guidance, which is fortunate since, unlike the IASB and FASB which make their guidance, in the public interest, freely available on line, the OECD hides its behind a paywall.

Currently, the criteria are orderly transactions between market participants.

Before IFRS 13 | ASC 820, arm's length transactions were the way to objectively determine value.

While orderly transactions between market participants have supplanted arm's length, remnants can still be found in some older guidance (i.e. IAS 24.23 or IAS 36.52 | ASC 460-10-30-2 or ASC 850-10-50-5).

Since IFRS 13 | ASC 820, transactions must be orderly instead.

IFRS 13 | ASC 820 define orderly: A transaction that assumes exposure to the market for a period before the measurement date to allow for marketing activities that are usual and customary for transactions involving such assets or liabilities; it is not a forced transaction (for example, a forced liquidation or distress sale).

In addition to being orderly, IFRS 13 | ASC 820 also requires the transactions to be between market participants, or buyers/sellers that are:

- independent

- knowledgeable

- willing and

- able

IFRS 13 | ASC 820 definition: Buyers and sellers in the principal (or most advantageous) market for the asset or liability that have all of the following characteristics:

- They are independent of each other, that is, they are not related parties, although the price in a related-party transaction may be used as an input to a fair value measurement if the reporting entity has evidence that the transaction was entered into at market terms

- They are knowledgeable, having a reasonable understanding about the asset or liability and the transaction using all available information, including information that might be obtained through due diligence efforts that are usual and customary

- They are able to enter into a transaction for the asset or liability

- They are willing to enter into a transaction for the asset or liability, that is, they are motivated but not forced or otherwise compelled to do so.

A stated interest rate could be unreasonable for various reasons.

The most common, assuming they are unrelated, the debtor and creditor have entered into a side agreement.

As outlined in ASC 835-30-25-6, if the interest associated with a liability is influenced by a side agreement, written or unwritten, it is adjusted to reflect the effect of that agreement.

ASC 835-30-25-6 (edited, emphasis added) states: A note issued solely for cash equal to its face amount is presumed to earn the stated rate of interest. However, in some cases the parties may also exchange unstated (or stated) rights or privileges, which are given accounting recognition by establishing a note discount or premium account. In such instances, the effective interest rate differs from the stated rate...

While ASC 835-30-25-4 to 11 discusses notes, by analogy the guidance applies to any (financial) liability.

As the name suggests, an unstated right or privilege is, well, unstated.

But, while the guidance talks about the chicken, the accountant is more interested in the egg.

While paragraph ASC 835-30-25-6 correctly points out that the unstated right or privilege is the cause of the unreasonable rate, since the unstated right of privilege is unstated, the accountant will only see the result: the unreasonable rate.

In other words, when a rate is unreasonable, the right or privilege that laid it needs to be tracked down.

To expand on this silly metaphor, since whomever hid the chicken may have gone out of their way to make sure it stays hidden, just like the T-X and Sandor Clegane's love child, a good accountant will never stop until they get their chicken.

On a serious note, finding, recognizing and measuring unstated right and privileges is always crucial, but especially so if the accountant has a Sarbanes-Oxley or similar obligation.

While IFRS 9 does not discuss "unstated rights or privileges," the guidance it does provide has the same effect.

IFRS 9.5.1.1 specifies that financial liabilities are measured at fair value (plus transaction costs in some situations).

IFRS 9.B5.1.1 elaborates on this general guidance by stating (edited): ... For example, the fair value of a long-term loan or receivable that carries no interest can be measured as the present value of all future cash receipts discounted using the prevailing market rate(s) of interest for a similar instrument...

Obviously, if a liability carries no interest, there has to be a reason. If the parties are unrelated, informed and acting voluntarily, the only possible reason could be an additional right or privilege.

By implication, the same logic applies if the stated (nominal or explicit) rate is not reasonable. If it is too low, the creditor has an additional right or privilege. If it is too high, the right or privilege belongs to the debtor.

Even if the borrower and lender are not market participants or have entered into a supplemental or unwritten agreement, present value will still reflect fair value. The only difference, that present value will be determined using an imputed interest rate rather than an explicit or implicit interest rate.

This issue is discussed in more detail in the following illustrations.

|

|

||

Interest |

|

||

Loan |

|

||

|

Cash |

|

24,716 |

If the payment is made before or at the end of a period, a single liability amortization entry can be made.

However, if the payment is made in the following period, the interest expense needs to be accrued:

12/31/X1 | 31.12.X1 |

|

|

|

Interest |

7,500 |

|

|

|

Loan |

|

7,500 |

1/1/X2 | 1.1.X2 |

|

|

|

Loan |

24,716 |

|

|

|

Cash |

|

24,716 |

If implicit interest is reasonable, it is recognized without adjustment.

If implicit interest is not reasonable, imputed interest is recognized instead.

As outlined in ASC 835-30, an interest rate must be reasonable, in that it must reflect an established exchange price for the liability. If not, a reasonable interest rate, one that does reflect this price, is imputed.

ASC 835-20 defines imputed interest rate: the interest rate that results from a process of approximation (or imputation) required when the present value of a note must be estimated because an established exchange price is not determinable and the note has no ready market.

Although the guidance specifically discusses notes, by analogy it applies to any financial liability.

ASC 835-20-25-4 to 11 go on to discuss various scenarios where imputation is necessary, such as when the agreement includes an unstated right or privilege, or the liability is incurred in exchange for a good or service.

Finally, ASC 835-20-25-12 and 13 suggest the methodology that should be used, but do not preclude different methodology if it can yield a more accurate result.

While "imputation" in only discussed in the ASC, IFRS 9 does provide guidance with a comparable result.

While IFRS 9 does not specifically mention imputation, IFRS 9.5.1.1 does require liabilities to be measured at fair value. Including its supplemental guidance, the standard yields results comparable to US GAAP.

For example, IFRS 9.B5.1.1 (edited, emphasis added) states: The fair value of a financial instrument at initial recognition is normally the transaction price... However, if part of the consideration given or received is for something other than the financial instrument, an entity shall measure the fair value of the financial instrument. For example, the fair value of a long-term loan or receivable that carries no interest can be measured as the present value of all future cash receipts discounted using the prevailing market rate...

In comparison ASC 835-30-25-6 (edited) states: A note issued solely for cash equal to its face amount is presumed to earn the stated rate of interest. However, in some cases the parties may also exchange unstated (or stated) rights or privileges, which are given accounting recognition by establishing a note discount or premium account. In such instances, the effective interest rate differs from the stated rate. For example, an entity may lend a supplier cash that is to be repaid five years hence with no stated interest. Such a non-interest-bearing loan may be partial consideration under a purchase contract for supplier products at lower than the prevailing market prices. In this circumstance, the difference between the present value of the receivable and the cash loaned to the supplier is appropriately regarded as an addition to the cost of products purchased during the contract term...

Although IFRS 9.B5.1.1 refers to both fair value and the prevailing market rate, while ASC 835-30-25-6 only to prevailing market prices, both require interest to reflect those prevailing market rates | prices. Whether the process is called imputation or something else is just semantics.

As XYZ and the bank transacted as market participants with no side agreement, 7,500 was reasonable.

Historically, arm’s length was the criterion for evaluating transactions and determining value.

Although the term appears in some (older) guidance, neither IFRS nor US GAAP have ever defined arm's length.

However, a good working definition is a price in an exchange between parties that are:

- unrelated

- fully informed, and

- acting voluntarily.

Also see one of the better summaries: link law.cornell.edu.

Note: the concept of arm's length features prominently in OECD, particularly transfer pricing, guidance. However, as the OECD’s purpose is to further cooperation between governments in developing common taxation policies, its influence on IFRS and US GAAP is derivative. For this reason, most accountants do not need to consider this guidance, which is fortunate since, unlike the IASB and FASB which make their guidance, in the public interest, freely available on line, the OECD hides its behind a paywall.

Currently, the criteria are orderly transactions between market participants.

Before IFRS 13 | ASC 820, arm's length transactions were the way to objectively determine value.

While orderly transactions between market participants have supplanted arm's length, remnants can still be found in some older guidance (i.e. IAS 24.23 or IAS 36.52 | ASC 460-10-30-2 or ASC 850-10-50-5).

Since IFRS 13 | ASC 820, transactions must be orderly instead.

IFRS 13 | ASC 820 define orderly: A transaction that assumes exposure to the market for a period before the measurement date to allow for marketing activities that are usual and customary for transactions involving such assets or liabilities; it is not a forced transaction (for example, a forced liquidation or distress sale).

In addition to being orderly, IFRS 13 | ASC 820 also requires the transactions to be between market participants, or buyers/sellers that are:

- independent

- knowledgeable

- willing and

- able

IFRS 13 | ASC 820 definition: Buyers and sellers in the principal (or most advantageous) market for the asset or liability that have all of the following characteristics:

- They are independent of each other, that is, they are not related parties, although the price in a related-party transaction may be used as an input to a fair value measurement if the reporting entity has evidence that the transaction was entered into at market terms

- They are knowledgeable, having a reasonable understanding about the asset or liability and the transaction using all available information, including information that might be obtained through due diligence efforts that are usual and customary

- They are able to enter into a transaction for the asset or liability

- They are willing to enter into a transaction for the asset or liability, that is, they are motivated but not forced or otherwise compelled to do so.

A stated interest rate could be unreasonable for various reasons.

The most common, assuming they are unrelated, the debtor and creditor have entered into a side agreement.

As outlined in ASC 835-30-25-6, if the interest associated with a liability is influenced by a side agreement, written or unwritten, it is adjusted to reflect the effect of that agreement.

ASC 835-30-25-6 (edited, emphasis added) states: A note issued solely for cash equal to its face amount is presumed to earn the stated rate of interest. However, in some cases the parties may also exchange unstated (or stated) rights or privileges, which are given accounting recognition by establishing a note discount or premium account. In such instances, the effective interest rate differs from the stated rate...

While ASC 835-30-25-4 to 11 discusses notes, by analogy the guidance applies to any (financial) liability.

As the name suggests, an unstated right or privilege is, well, unstated.

But, while the guidance talks about the chicken, the accountant is more interested in the egg.

While paragraph ASC 835-30-25-6 correctly points out that the unstated right or privilege is the cause of the unreasonable rate, since the unstated right of privilege is unstated, the accountant will only see the result: the unreasonable rate.

In other words, when a rate is unreasonable, the right or privilege that laid it needs to be tracked down.

To expand on this silly metaphor, since whomever hid the chicken may have gone out of their way to make sure it stays hidden, just like the T-X and Sandor Clegane's love child, a good accountant will never stop until they get their chicken.

On a serious note, finding, recognizing and measuring unstated right and privileges is always crucial, but especially so if the accountant has a Sarbanes-Oxley or similar obligation.

While IFRS 9 does not discuss "unstated rights or privileges," the guidance it does provide has the same effect.

IFRS 9.5.1.1 specifies that financial liabilities are measured at fair value (plus transaction costs in some situations).

IFRS 9.B5.1.1 elaborates on this general guidance by stating (edited): ... For example, the fair value of a long-term loan or receivable that carries no interest can be measured as the present value of all future cash receipts discounted using the prevailing market rate(s) of interest for a similar instrument...

Obviously, if a liability carries no interest, there has to be a reason. If the parties are unrelated, informed and acting voluntarily, the only possible reason could be an additional right or privilege.

By implication, the same logic applies if the stated (nominal or explicit) rate is not reasonable. If it is too low, the creditor has an additional right or privilege. If it is too high, the right or privilege belongs to the debtor.

As a general rule:

- Commercial emprises and their banks are independent (unrelated).

- Unless the enterprise has committed bank fraud, it and its bank are knowledgeable (fully informed).

- Ability is a non-issue.

- It is hard to imagine a scenario where an enterprise or its bank would act unwillingly.

IFRS 13 | ASC 820 deals with fair value which is the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability. Consequently, the guidance needs to consider the future. One way future value can be determined is a future exchange. In this situation, the ability of the parties to act in the future needs to be evaluated. If the transaction has already occurred, the parties were obviously able. The only reason it appears in this list, it is part of the definition of market participants (above), so cannot be omitted.

Finally, while conceivable, in jurisdictions with adequate regulation, banks do not enter into unwritten agreements with their clients. So, as a general rule, whatever interest a bank and its client agree to is, a priori, reasonable.

As outlined in ASC 835-30-55-2, financial liabilities are subsequently measured using the effective interest method:

While IFRS 9 does not explicitly state that the effective interest method is required, it does specify amortised cost accounting for all financial liabilities, and effective interest is part of the definition of amortised cost.

Technically, as outlined in IFRS 4.2.1, amortized cost accounting is required for all financial liabilities except: (a) those measured at FVtP&L, (b) those that arise when a transfer of a financial asset does not qualify for derecognition or when the continuing involvement approach applies, (c) financial guarantee contracts, (d) commitments to provide a loan at a below-market interest rate and (e) contingent consideration recognised by an acquirer in a business combination.

Note: the interest method mentioned in US GAAP is the same as the effective interest method mentioned in IFRS.

P |

Loan balance |

Interest rate |

Interest expense |

Cash flow |

Amortization |

A |

B = B(B+1) - F |

C |

D = B x C |

E |

F = E - D |

1 |

100,000 |

7.5% |

7,500 |

24,716 |

17,216 |

2 |

82,784 |

7.5% |

6,209 |

24,716 |

18,508 |

3 |

64,276 |

7.5% |

4,821 |

24,716 |

19,896 |

4 |

44,380 |

7.5% |

3,329 |

24,716 |

21,388 |

5 |

22,992 |

7.5% |

1,724 |

24,716 |

22,992 |

|

|

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|||||

12/31/X5 | 31.12.X5 |

|

|

|

Interest |

1,724 |

|

|

Loan |

22,992 |

|

|

|

Cash |

|

24,716 |

To draft its interim (quarterly) financial statements, XYZ recognized:

3/31/X1 | 31.3.X1 |

|

|

|

Interest |

|

||

|

Loan |

|

1,875 |

If the payment is annual, interest will accrue on a straight-line basis throughout the year.

The same would apply to, for example, quarterly payments accrued on a monthly basis.

Floating interest (variable payments)

Same facts except the payment was tied to a market interest rate and reset annually.

As market interest rates change, the payments calculated on the basis of these rates also change .

However, as outlined in IFRS 9.B5.4.5, these changes will not, as a rule, lead to liability remeasurement.

IFRS 9 distinguishes revisions to cash flow estimates caused by changes in interest rates (IFRS 9.B5.4.5) and those caused by other changes (IFRS 9.B5.4.6), with the latter subject to additional guidance, which may lead to a remeasurement of the liability in some circumstances.

While US GAAP does not provide similar, explicit guidance, its overall guidance yields a comparable result.

12/31/X1 | 31.12.X1 |

|

|

|

Interest |

7,500 |

|

|

Loan |

|

||

|

Cash |

|

24,716 |

P |

Loan balance |

Interest rate |

Interest expense |

Cash flow |

Amortization |

A |

B = B(B+1) - F |

C |

D = B x C |

E |

F = E - D |

1 |

100,000 |

7,500 |

24,716 |

17,216 |

|

2 |

82,784 |

7.5% |

6,209 |

24,716 |

18,508 |

3 |

64,276 |

7.5% |

4,821 |

24,716 |

19,896 |

4 |

44,380 |

7.5% |

3,329 |

24,716 |

21,388 |

5 |

22,992 |

7.5% |

1,724 |

24,716 |

22,992 |

|

|

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|||||

The discount rate used to amortize the liability in the first period, is the initial implicit rate.

The simplest way to calculate this rate is Excel's =RATE function: 7.5%=RATE(5,-24716,100000,0,0).

Alternatively, the =IRR or =XIRR functions can be used:

P |

|

|

Cash flow |

A |

|

|

B |

0 |

|

|

(100,000) |

1 |

|

|

24,716 |

2 |

|

|

24,716 |

3 |

|

|

24,716 |

4 |

|

|

24,716 |

5 |

|

|

24,716 |

|

|

|

7.5%=IRR(B0:B5) |

P |

Date |

|

Cash flow |

A |

B |

|

C |

0 |

1/1/X0 |

|

(100,000) |

1 |

1/1/X1 |

|

24,716 |

2 |

1/1/X2 |

|

24,716 |

3 |

1/1/X3 |

|

24,716 |

4 |

1/1/X4 |

|

24,716 |

5 |

1/1/X5 |

|

24,716 |

|

|

|

7.5%=XIRR(B0:B5,C0:C5,0.1) |

For X2, the payment was 24,994.

To calculate the payment for the remaining 4 years, the lender used the following formula (in excel syntax):

24994=ROUND(82784/((1-(1/(1+8%)^4))/8%),0)

12/31/X2 | 31.12.X2 |

|

|

|

Interest |

6,209 |

|

|

Loan |

|

||

|

Cash |

|

24,994 |

For the second period, XYZ updated the amortization schedule to reflect the change in the payment.

P |

Loan balance |

Interest rate |

Interest expense |

Cash flow |

Amortization |

A |

B = B(B+1) - F |

C |

D = B x C |

E |

F = E - D |

1 |

100,000 |

7.5% |

7,500 |

24,716 |

17,216 |

2 |

82,784 |

6,209 |

24,994 |

18,371 |

|

3 |

64,412 |

8% |

4,821 |

24,994 |

19,841 |

4 |

44,571 |

8% |

3,329 |

24,994 |

21,428 |

5 |

23,143 |

8% |

1,724 |

24,994 |

23,143 |

|

|

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|||||

In the second period, XYZ adjusted the implicit rate to reflect the change in the payments.

The simplest way to calculate an implicit rate is Excel's =RATE function: 8%=RATE(4,-24994,82784,0,0).

Alternatively, the =IRR or =XIRR functions can be used:

P |

|

|

Cash flow |

A |

|

|

B |

0 |

|

|

(82,784) |

1 |

|

|

24,994 |

2 |

|

|

24,994 |

3 |

|

|

24,994 |

4 |

|

|

24,994 |

|

|

|

8%=IRR(B0:B5) |

P |

Date |

|

Cash flow |

A |

B |

|

C |

0 |

1/1/X1 |

|

(82,784) |

1 |

1/1/X2 |

|

24,994 |

2 |

1/1/X3 |

|

24,994 |

3 |

1/1/X4 |

|

24,994 |

4 |

1/1/X5 |

|

24,994 |

|

|

|

8%=XIRR(B0:B5,C0:C5,0.1) |

In the next three periods the payments were: 25,107, 24,935 and 24,878.

P |

Loan balance |

Interest rate |

Interest expense |

Cash flow |

Amortization |

A |

B = B(B+1) - F |

C |

D = B x C |

E |

F = E - D |

1 |

100,000 |

7.5% |

7,500 |

24,716 |

17,216 |

2 |

82,784 |

8% |

6,209 |

24,994 |

18,371 |

3 |

64,412 |

8.25% |

5,314 |

25,107 |

19,793 |

4 |

44,619 |

8.25% |

3,681 |

25,107 |

21,426 |

5 |

23,193 |

8.25% |

1,913 |

25,107 |

23,193 |

|

|

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|||||

P |

Loan balance |

Interest rate |

Interest expense |

Cash flow |

Amortization |

A |

B = B(B+1) - F |

C |

D = B x C |

E |

F = E - D |

1 |

100,000 |

7.5% |

7,500 |

24,716 |

17,216 |

2 |

82,784 |

8% |

6,209 |

24,994 |

18,371 |

3 |

64,412 |

8.25% |

5,314 |

25,107 |

19,793 |

4 |

44,619 |

7.75% |

3,458 |

24,935 |

21,477 |

5 |

23,142 |

7.75% |

1,793 |

24,935 |

23,142 |

|

|

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|||||

P |

Loan balance |

Interest rate |

Interest expense |

Cash flow |

Amortization |

A |

B = B(B+1) - F |

C |

D = B x C |

E |

F = E - D |

1 |

100,000 |

7.5% |

7,500 |

24,716 |

17,216 |

2 |

82,784 |

8% |

6,209 |

24,994 |

18,371 |

3 |

64,412 |

8.25% |

5,314 |

25,107 |

19,793 |

4 |

44,619 |

7.75% |

3,458 |

24,935 |

21,477 |

5 |

23,142 |

7.5% |

1,736 |

24,878 |

23,142 |

|

|

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|||||

Serial repayment, effective interest

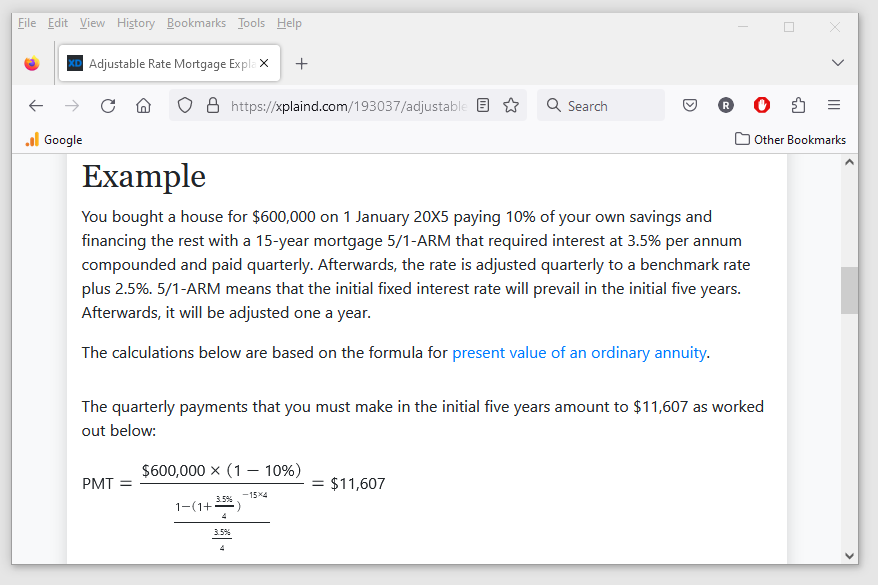

1/1/X1, XYZ borrowed 100,000 from a non-bank lender.

While the loan agreement explicitly stated a 7.5% annual interest rate, it also demanded monthly payments of 2,004.

As the implicit rate was 7.763%, XYZ amortized the liability using that effective rate.

In Excel syntax: 7.763%= ((1+ROUND(RATE(60,-2004,100000,0,0), 5))^12) – 1

If, for the sake or accuracy, exact dates need to be considered, it can also be calculated:

P |

Date |

|

Cash flow |

A |

B |

|

C |

0 |

1/1/X0 |

|

(100,000) |

1 |

2/1/X1 |

|

2,044 |

2 |

3/1/X2 |

|

2,044 |

|

- |

- |

|

- |

|

59 |

12/1/X4 |

|

2,044 |

|

60 |

1/1/X5 |

|

2,044 |

|

|

|

7.76011794805527%=XIRR(B0:B5,C0:C5,0.1) |

Note: rather than calculate payments properly, the lender used the approach suggested here.

The proper way to calculate monthly payments based on an annual rate is (in Excel syntax):

1,992.12=round(100000/((1-(1/(1+((1+7.5%)^(1/12)-1))^(5*12)))/((1+7.5%)^(1/12)-1)),2).

The reason? An annual rate should not be converted to a monthly rate by simple division, but with some mathematical finesse (in Excel syntax):

0.604%=ROUND((1+7.5%)^(1/12)-1,5)

Or 0.604491902429172%=(1+7.5%)^(1/12)-1, if more accuracy is desired.

Obviously, it is possible to convert an annual rate, as suggested by this site, to an interim rate by simple division.

Using this approach will yield (in Excel syntax) monthly payments of:

2,003.79=round(100000/((1-(1+7.5%/12)^(-5*12))/(7.5%/12)),2)

Whether a lender would choose this approach out of a lack of mathematical finesse or because it leads to higher payments is a question. But, it does happen.

For example, a broker with whom the author has experience calculates its margin interest this way. Given that running brokerages usually requires some mathematical finesse, the answer to the question, in this particular situation, seems fairly obvious.

The terms implicit and effective can be used interchangeably.

Specifically, US GAAP uses implicit interest to define effective interest, making the two synonyms.

ASC Master Glossary (edited): The rate of return implicit in the financial asset, that is, the contractual interest rate adjusted for any net deferred fees or costs, premium, or discount existing at the origination or acquisition of the financial asset...

Interestingly, the definition (as updated by ASU 2016-13) addresses the issue by referring to a financial asset.

In contrast, the previous definition referred to a loan: The rate of return implicit in the loan, that is, the contractual interest rate adjusted for any net deferred loan fees or costs, premium, or discount existing at the origination or acquisition of the loan.

From a practical perspective however, it make no difference as effective interest is determined the same way in both situations: by evaluating cash flow.

Interestingly, besides defining the term, the IFRS 9 definition also explains how to calculate effective interest.

IFRS 9 Defined terms (edited): ... When calculating the effective interest rate, an entity shall estimate the expected cash flows by considering all the contractual terms of the financial instrument (for example, prepayment, extension, call and similar options) but shall not consider the expected credit losses. The calculation includes all fees and points paid or received between parties to the contract that are an integral part of the effective interest rate ..., transaction costs, and all other premiums or discounts. There is a presumption that the cash flows and the expected life of a group of similar financial instruments can be estimated reliably. However, in those rare cases when it is not possible to reliably estimate the cash flows or the expected life of a financial instrument (or group of financial instruments), the entity shall use the contractual cash flows over the full contractual term of the financial instrument (or group of financial instruments).

Presumably because it considers it obvious, the ASC does not go into such detail. Thus, as they more or less describe how it is done in practice anyway, the instructions in IFRS 9 can be considered in a US GAAP context, especially since this is suggested in ASC 105-10-05-3.d.

While IFRS does not incorporate implicit into its definition, the definition itself yields a comparable result.

IFRS 9 Defined terms (edited): The rate that exactly discounts estimated future cash payments or receipts through the expected life of the financial asset or financial liability to the gross carrying amount of a financial asset or to the amortised cost of a financial liability...

1/31/X1 | 31.1.X1 |

|

|

|

Interest |

625 |

|

|

Loan |

|

||

|

Cash |

|

2,004 |

As the 2,004 payment implied a monthly rate of 0.625%, XYZ used that rate to amortize the liability.

P |

Loan balance |

Interest rate |

Interest expense |

Cash flow |

Amortization |

A |

B = B(B+1) - F |

C |

D = B x C |

E |

F = E - D |

1 |

100,000 |

0.625% |

625 |

2,004 |

1,379 |

2 |

98,621 |

0.625% |

616 |

2,004 |

1,387 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

59 |

3,970 |

0.625% |

25 |

2,004 |

1,979 |

60 |

1,991 |

0.625% |

12 |

2,004 |

1,991 |

|

|

|

|

|

100,000 |

|

|||||

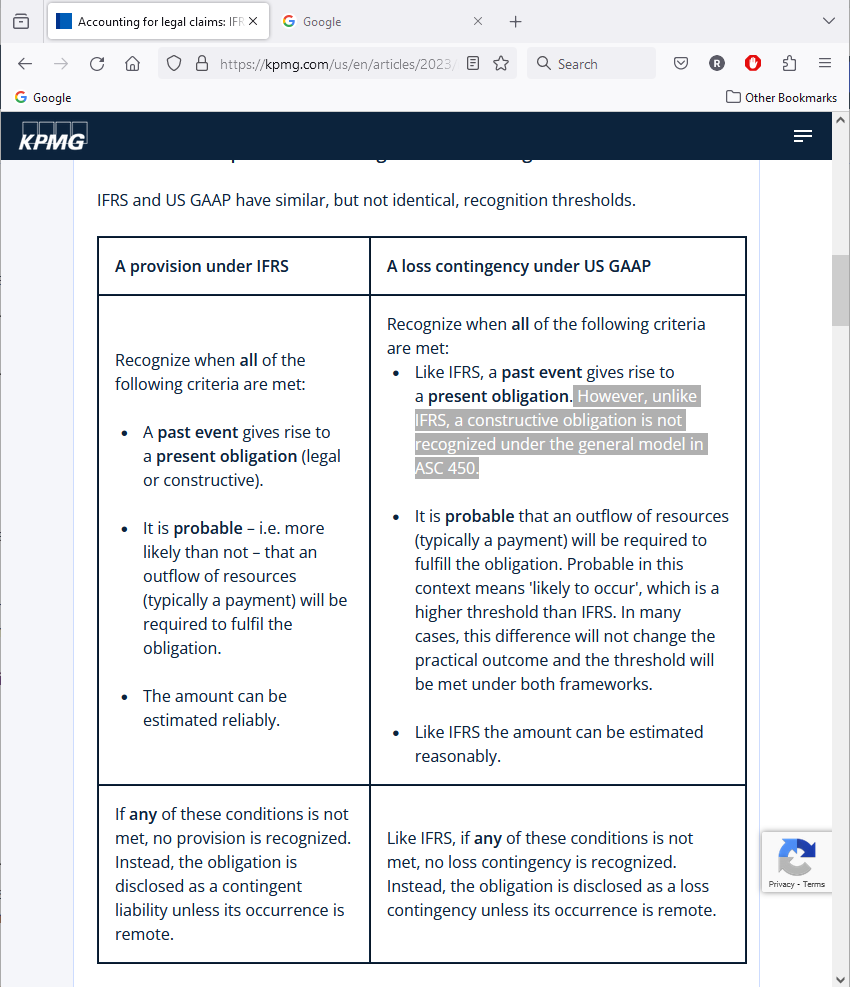

Provisions | Contingent liabilities

At first glance, IFRS and US GAAP appear incompatible.

IFRS 37 distinguishes between provisions, contingent liabilities and contingent assets. More importantly, it does not allow either contingent liabilities or contingent assets to be taken to the balance sheet.

IAS 37.27/31 specify that a contingent liability / contingent asset may not be recognized.

Except in a business combination.

As outlined in IFRS 3.23, if a contingent liability arises from a business combination, it is recognized "...if it is a present obligation that arises from past events and its fair value can be measured reliably" irrespective of the guidance provided by IAS 37.27 to 30.

However, this only applies to contingent liabilities. Contingent assets, as outlined in IFRS 3.23A, are not recognized.

IAS 37.28/34 specify that a contingent liability / contingent asset is disclosed unless remote / if probable.

In contrast, ASC 450 only distinguishes between contingent liabilities and contingent assets. More importantly, it requires contingent liabilities to be taken to the balance sheet.

Unlike IFRS, which addresses related issues in a single standard, US GAAP breaks them down into:

- ASC 410 - Asset Retirement and Environmental Obligations

- ASC 420 - Exit or Disposal Cost Obligations (a.k.a. restructuring)

- ASC 440 - Commitments

- ASC 450 - Contingencies and

- ASC 460 - Guarantees (including warrantees).

Of these, ASC 450 provides the general, overall guidance.

Technically, ASC 450 discusses loss contingencies and gain contingencies not contingent liabilities and contingent assets. However, this difference is merely semantic.

FAS 5 was published in 1975, preceding the conceptual framework. As such, it's language reflects the previous income/expense perspective rather than a contemporary asset/liability view. When it was codified as ASC 450, its terminology was not updated.

An interesting analysis of some implications this change can be found in this dissertation (link / local link).

In any event, as contingent liabilities/assets and loss/gain contingencies are two sides of the same coin, it makes little practical difference which term is used.

ASC 450-20-25-2 specifies that loss contingencies are taken to the balance sheet if probable and estimable.

ASC 450-30-25-1 specifies that gain contingencies are not reflected on the balance sheet until realized (no longer contingent).

ASC 450-30-50-1 specifies that gain contingencies may be disclosed if care is taken to not misrepresent the likelihood of their realization.

While differences do exist, that IFRS addresses provisions while US GAAP contingent liabilities is not one of them.

The most obvious difference, while IFRS addresses related issues in one standard, US GAAP breaks them into Asset Retirement and Environmental Obligations (ASC 410), Exit or Disposal Cost Obligations (ASC 420), Commitments (ASC 440), Contingencies (ASC 450) and Guarantees (ASC 460).

ASC 410 deals with both Asset Retirement Obligations (410-20) and Environmental Obligations (410-30).

It also includes an overall subtopic, but ASC 410-10 merely states: the sole purpose of the Overall Subtopic is to explain the differences between the other two Subtopics.

Note: asset retirement obligations are illustrated in the self-constructed asset section of this page.

Commonly known as restructuring, a term used by IAS 37, US GAAP prefers the sound of:

Exit or Disposal Cost Obligations.

As they are related, commitments and contingencies are practically always reported as a single balance sheet item.

This common practice is also reflected in FASB XBRL which defines CommitmentsAndContingencies: "(1) purchase or supply arrangements that will require expending a portion of its resources to meet the terms thereof, and (2) is exposed to potential losses or, less frequently, gains, arising from (a) possible claims against a company's resources due to future performance under contract terms, and (b) possible losses or likely gains from uncertainties that will ultimately be resolved when one or more future events that are deemed likely to occur do occur or fail to occur."

ASC 450-20-05-10 gives examples of loss contingencies:

- Injury or damage caused by products sold

- Risk of loss or damage of property by fire, explosion, or other hazards

- Actual or possible [a.k.a. unasserted] claims and assessments

- Threat of expropriation of assets

- Pending or threatened litigation

ASC 460 provides guidance on guarantees: an obligation to stand ready to perform (460-10-25-2.a) and a contingent obligation to make future payments (460-10-25-2.b).

It also includes a sub-section devoted to Product Warranties. As product warranties are by far the more common, they are illustrated here and, in more detail, on the receivables and revenue page.

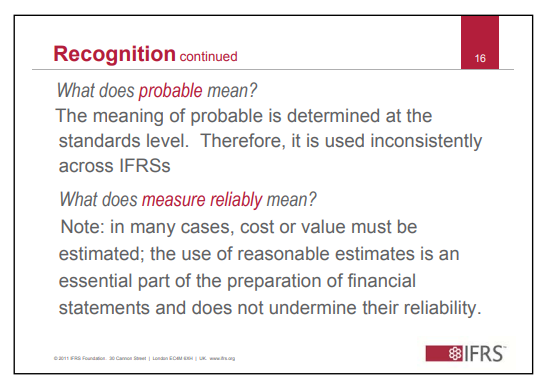

However, the most important difference is not specific to provisions | contingent liabilities at all. Instead, the way IFRS and US GAAP interpret the word probable is pervasive, affecting practically every issue involving uncertainty.

In the context of provisions | contingent liabilities, this difference implies the obligation could appear on the balance sheet sooner under IFRS than US GAAP (if at all).

It is possible that US GAAP's higher threshold could lead an entity to skip the contingent liability phase altogether.

For example, the inherent uncertainly of litigation means an entity could estimate the probability it will prevail at 50/50 right up until the verdict is read. In such a situation, it would never recognize a contingent liability, but rather a regular liability, but only if it were found liable.

As a general rule, the IFRS threshold is 50%, while US GAAP sets a higher bar at 75% to 80%.

In the past, the IASB used to hold staff days for teachers where academics from all over the world had the opportunity to interact with the IASB staff. During one such meeting in 2012, the topic of probability came up. As the information provided was not particularly satisfying, the attendees asked the staff member in charge "so what are we supposed to tell out students?"

Source: local link.

Unfortunately, Google is no longer able to find a link to this file on the IASB's web site.

The staff member replied: "the conceptual framework does not quantify the term probable and it is not used consistently throughout the standards."

Being academics, we had been able to read this for ourselves, so we requested a real answer.