Despite its claim, the guidance on inventory is not about inventory.

IAS 2 is titled Inventories.

ASC 330 is titled Inventory.

IAS 2 begins by stating: the objective of this standard is to prescribe the accounting treatment for inventories...

ASC 330 begins by stating: the inventory topic addresses the accounting principles and reporting practices applicable to inventory.

These statements are true, but they are not correct.

Ontologically, the guidance does not actually address inventory, but what inventory becomes when sold.

At a typical manufacturer, inventory may represent perhaps 10% of total assets. At a service provider, if it reports inventory at all, it may be even less. Cost of sales, on the other hand, easily comprises 50% or 60% of a manufacturer's total expenses. At a service provider, it is often considerably more.

Inventory is expensive. Inventory ties up capital. Consequently, most industrial companies go to great lengths to keep inventory low. So, when it comes to reporting inventory on the balance sheet, there is not much to report, especially as many companies like to clear out old stock right before they take physical inventory to minimize the time and effort this task wastes.

Obviously, as with any general rule, exceptions exist.

Some companies, particularly those that buy commodities, have vast stockpiles because, as everyone knows, when commodity prices fluctuate unpredictably, buying vast quantities when the price is right makes sense, or one could simply enter into a derivatives contract, but that is a different issue.

In any event, most companies do not buy commodities. Most companies buy semi-finished goods, the suppliers of which are happy, with gentle persuasion, to deliver just in time.

While not impossible, for example a provider of repair services may have some spare parts inventory, most service providers do not recognize or report inventory. Instead, they capitalize service costs as contract assets or accruals.

Cost of sales is the broadest, comprising both cost of goods sold and cost of services rendered. Cost of goods sold may also be broken down into cost of products sold and cost of merchandise sold.

However, as they are most common, only COS and COGS are universally recognized acronyms.

Note: FASB XBRL uses a Cost of Revenue (CostOfRevenue) in place of Cost of Sales (though it does include a CostOfSalesMember). It then disaggregates Cost of Revenue into Cost of Product and Service Sold (CostOfGoodsAndServicesSold) items such as FinancingInterestExpense or PolicyholderBenefitsAndClaimsIncurredNet. IASB XBRL does include a Cost of sales (CostOfSales) item. It also goes into some, althogh diffrent, detail CostOfMerchandiseSold, CostOfPurchasedEnergySold, CostOfSalesHotelOperations, CostOfSalesFoodAndBeverage, CostOfSalesRoomOccupancyServices, etc.

Similarly, from the user's perspective, inventory means nothing. Cost of sales means everything.

Assuming these two companies are otherwise comparable:

Same industry, customer base, and product type.

Obviously, in a real-life scenario, a deeper analysis of the expense structure would be critical. Particularly, it would be necessary to determine if the difference was not caused by research and development or similar, future-useful costs (e.g. sales or perhaps marketing).

While such an analysis is effortless for entities applying US GAAP, it is practically impossible for entities applying IFRS, unless domiciled in a jurisdiction that requires information beyond that required by IFRS itself.

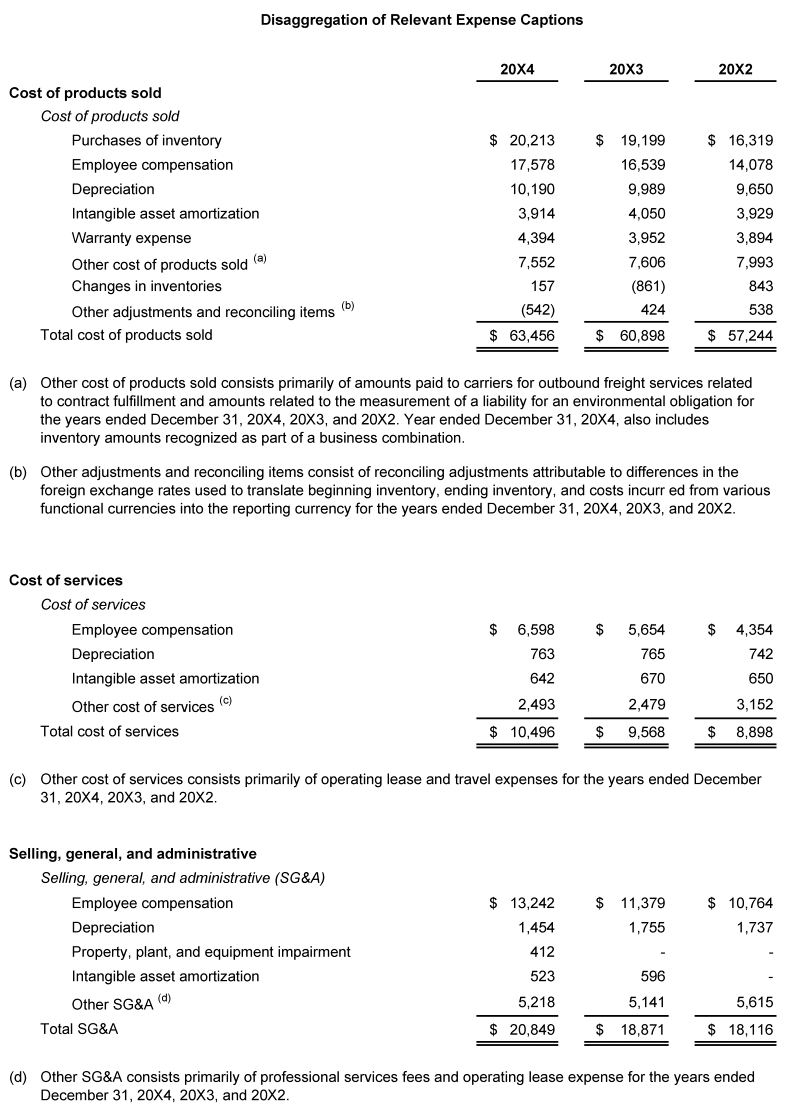

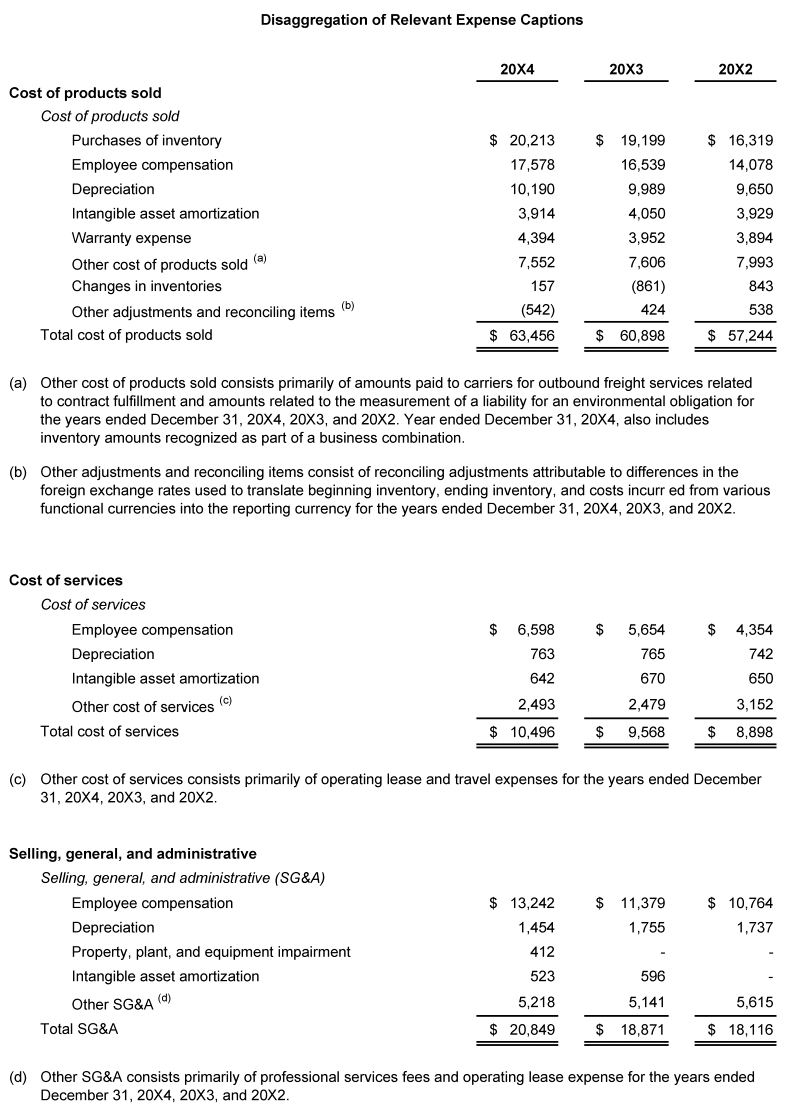

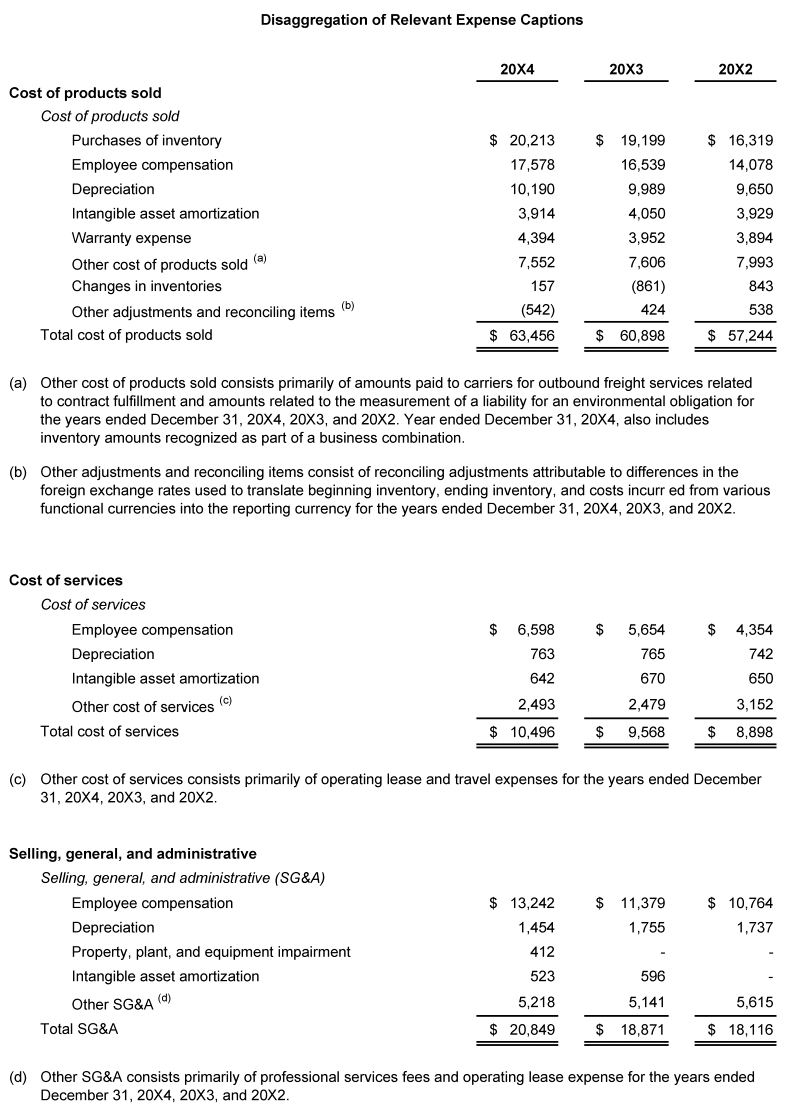

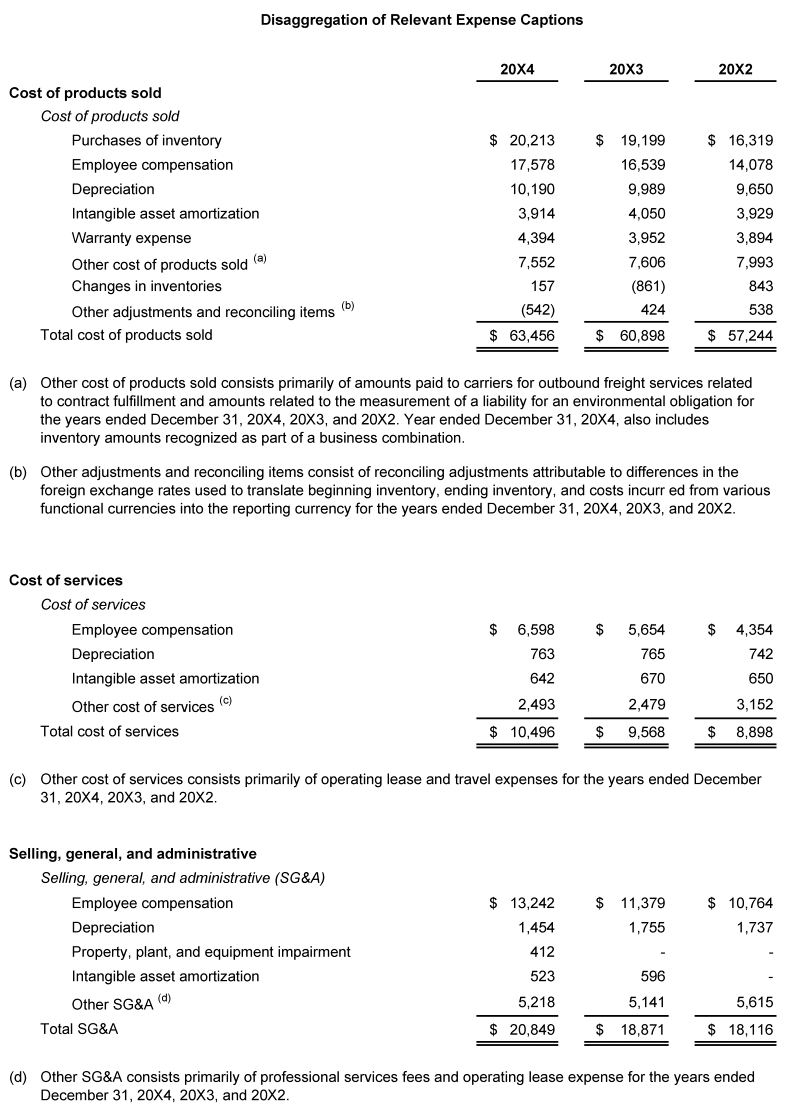

To codify best practice, from 12/16/2026 ASC 220-40-55-11 mandates a granular breakdown of expenses on the level of this illustration:

Editorial comment: while certainly not the only cause, the relative friendliness/unfriendliness of the regulatory environment towards individual investors, investors lacking special privileges, helps explain the relative underperformance of non-US capital markets versus US capital markets, where individual investors feel confident in a level playing field. This is particularly evident in the EU, which has the unenviable track record of being regulatory-friendly towards a select segment of the investing community while leaving the remainder, particularly individuals, with such limited access to actionable information that they feel compelled to entrust their capital allocation decisions to institutional investors. Most regrettably, this preferential treatment of a select investor class shows no signs of being adjusted in the near future.

If it did, the European Commission, as the single largest contributor to the IASB's budget with influence over its decision-making process beyond what the EU's global economic significance would suggest, could have encouraged the standard setter to include guidance comparable to ASC 220-40-55-11 in IFRS 18. It did not. So while IFRS 18 aimed to bring IFRS reporting requirements into the twenty-first century, it ultimately fell short of the mark.

|

ABC |

XYZ |

|

|

Cash |

6 |

7 |

|

Receivables |

8 |

8 |

|

Inventory |

6 |

5 |

|

PP&E |

80 |

80 |

|

Assets |

100 |

100 |

|

Payables |

10 |

10 |

|

Debt |

40 |

40 |

|

Equity |

50 |

50 |

|

Liabilities and equity |

100 |

100 |

|

Revenue |

100 |

100 |

|

Cost of sales |

60 |

40 |

|

Gross profit |

40 |

60 |

|

Administrative expenses |

30 |

50 |

|

Net income |

10 |

10 |

An auditor would likely reach a conclusion such as this.

A common misconception is that auditors and accountants are locked into an adversarial dichotomy.

Assuming both are reasonable professionals, this is not the case. While auditors tend to approach their tasks with a more detached view and clinical precision, they share the same goal as accountants: ensuring the financial report paints a faithful portrait of a company's financial position and results.

Put another way, both seek to ensure that the individuals charged with administering a company's assets (management) are held accountable to those contributing those assets (shareholders and creditors).

Since they share this common aim, seasoned auditors and seasoned accountants typically find common ground and collaborate to ensure the company's financial reports serve their intended purpose.

While this generalization generally holds up in an IFRS | US GAAP context where IFRS | US GAAP generally exist to inform investors and creditors, it may break down in jurisdictions where national GAAP generally exists to establish taxable income.

In these jurisdictions an auditor's insistence on an overly rigorous application of accounting law can have the effect of maximizing taxable income and tax expense. For this reason, the working relationship between accountants and auditors in such jurisdictions is generally less collegial than in jurisdictions where this is not the situation.

Executive Summary

A comparative review of ABC and XYZ, two manufacturing entities with comparable asset bases and operating environments, indicates that inventory variances are immaterial. The primary differentiator is cost of sales, which has significant implications for operational efficiency, management effectiveness, and governance-related risks.

1. Inventory and Cost of Sales

The difference in inventory levels between ABC (6% of assets) and XYZ (5%) is not material. Without additional context, specifically cost of sales, inventory disclosures under IAS 2 | ASC 330 offer limited insight into operational performance and may detract focus from more relevant indicators.

Cost of sales is the key difference. ABC's cost of sales stands at 60% of revenue, compared to 40% for XYZ. Given similar supplier and labor pool, this suggests differences in process efficiency, proprietary technology, or management practices. Under US GAAP, a more detailed cost of sales breakdown is required, facilitating direct analysis of these differences. Under IFRS, such granularity is not mandated. If XYZ reports under both US GAAP and IFRS, e.g. for a dual US and EU filing, audit procedures need to address both frameworks. Where IFRS guidance fails to dictate sufficient detail, supplementary procedures, including analysis or estimation, would be necessary to validate conclusions and ensure consistency.

2. Management Assessment

ABC's sustained operational inefficiency, despite comparable resources, indicates potential deficiencies in management effectiveness or operational capability. This is unlikely attributable to lack of education, experience, motivation, or ambition, as such shortcomings rarely coincide with senior management appointments. The root cause likely relates to limitations in strategic decision-making or operational execution. While increased diligence may temporarily mask these deficiencies, they result in persistent underperformance, as evidenced by comparative metrics. Historical data supports management quality as a critical determinant of economic outcomes.

3. Agency Risk and Governance

XYZ, despite superior operational efficiency, reports elevated administrative expenses relative to peers. This may indicate agency risk, where management prioritizes personal interests over those of shareholders. Verification of board approval for any excessive remuneration is essential. Potential for future restitution or corrective action should be monitored unless operational inefficiencies are promptly addressed.

4. Investor Implications and Market Impact

A rational investor may view XYZ's predictable management behavior as less detrimental than ABC's persistent operational shortcomings, which often lead to erratic and value-destructive outcomes.

Recognition of XYZ's operational strengths could attract unsolicited acquisition interest, given typical earnings-based valuation multiples. Acquisitions may be structured via share exchange rather than cash, enhancing financial leverage. Post-acquisition restructuring would likely involve management replacement and redundancy elimination, yielding rapid profitability gains. While beneficial to stakeholders, such events may curtail existing relationships.

Alternatively, the threat of acquisition may prompt XYZ's board to initiate defensive restructuring, implementing efficiency measures to forestall external intervention. Although potentially less effective than a full takeover, this would likely preserve current engagements.

5. Financial Reporting Risk: Expense Classification

Management may attempt to conceal inefficiencies through accounting policy choices, notably reclassifying administrative expenses as cost of sales. Given the scale of cost of sales, such reclassifications may be less conspicuous and obscure operational weaknesses, reducing attractiveness as a takeover or restructuring candidate. Audit efforts should prioritize verifying the accuracy and appropriateness of cost of sales classification to detect potential misstatements.

An investor would, on the other hand, be thinking:

Inventory is pointless.

What is the point in knowing ABC has 1% more inventory than XYZ?

Yes, it is a fact, but what useful information does it bring me? If I don't also look at cost of sales, the information presented on the basis of IAS 2 | ASC 330 is not only useless but, because it can distract me from the real issue, less than useless.

Cost of sales is not pointless.

XYZ is clearly better at its job than ABC.

Since both have access to more or less the same suppliers and labor pool, it has to be the technology. Most likely, XYZ developed its own, while ABC went off-the-shelf so had to plug the gap with brute force. If the companies reported per US GAAP, I could confirm just by looking at the granular breakdown US GAAP requires (above). Under IFRS, I have to guess, but I'm still pretty confident I can guess right.

ABC's management has a fatal flaw.

Let us see, if ABC's management were competent, ABC would be able to manufacture as effectively as XYZ. So, why is ABC's management incompetent?

Could it be lack of education? Hardly, uneducated people rarely rise to top managerial positions.

Could it be lack of experience? Hardly, inexperienced people rarely rise to top managerial positions.

Could it be lack of motivation? Hardly, unmotivated people rarely rise to top managerial positions.

Could it be lack of ambition? Hardly, unambitious people rarely rise to top managerial positions.

Could it be laziness? ...

So, what could it be?

Oh I know, birth defect.

Unfortunately, some people are born with a fatal flaw. This flaw is so fatal education, experience, motivation, ambition and the willingness to work 16-hours 7 days a week do nothing to help. In fact, they make it even more fatal because they hide it until it's too late.

Yes, I realize fatal is binary. But, sometimes, literary flair trumps the desire for linguistic accuracy.

More fatal. I'm not trying to be funny here, it's just that I couldn't actually care less if some company lives, or dies a horrible death. Not my problem. It only becomes my problem if I happen to have bought their shares. At that point I do care. A lot.

So, what is this flaw?

Inadequate IQ.

Combine education, experience, motivation, ambition and work ethic with the inborn inability to achieve the above-par cognitive results expected of successful managers and what do you get? The corporate structure is designed to filter the industrious stupid before they can cause real harm. But, once in a while, the Peter Principle leads all the way to the corner office.

Does anyone remember a company, once America's industrial leader and one of the select few to earn a AAA credit rating? Then, new management took over. Or the company, once America's technology leader. Then, new management took over. Or the company that invented digital photography but then said, 'Nah.' Sometimes the company can bounce back. Sometimes not.

The trick is identifying an idiot before it hits the ticker.

Fortunately, cost of sales never lies. True, sometimes it tells the truth a bit too late, but it never lies.

So does XYZ's, just different.

Sometimes, managers hired to run companies forget who they work for.

Even some exceedingly bright and highly competent managers, managers who run the company brilliantly, like the CEO who took home an extra $600 million, including the $2 million for a birthday bash for his wife, forget the company's profits are not their profits. They are shareholder profits.

BTW, this is also why I hesitate to invest in companies run by founders. When the CEO is also a major shareholder, he or she can almost always get the board of directors he or she desires. So, until they move on, they can drain all the profit from the company (like, for example, the world's richest man continually tries to do).

The flip side, when a founder leaves and professional management takes over, the company's vision may become clouded. It may forget who it actually serves. As a result, it may set off down the path to short-term profits speculators so love.

Not that I'm pointing fingers, but submerging users in unsolicited, superfluous, irrelevant search results to the point of fatal respiratory impairment is not a sustainable business model. Anyone remember Myspace?

But I digress.

Can a penchant for thievery be fixed, or is this flaw as insurmountable as stupidity?

Personally, I don't think it is possible to remagnetize a faulty moral compass. It can be punished, and investors restituted (if lucky), but people do not change. Once a thief, always a thief.

Time to load up on some options.

As any rational investor knows, no cure for either insufficient IQ or faulty moral compass exists.

But, unlike an idiot, a thief one can work with. Not only are they smart enough to know not to steal too much, but they will act consistently. And predictability has value.

Idiots, on the other hand, being idiots, act like idiots. This makes them unpredictable. About the last thing one wants to see coming over the Bloomberg screen is that management's latest, greatest idea: let's spend $11.1 billion to buy some Autonomy.

But that is not the real issue.

Assuming the outlined above information became known. A big if, but if it did, a third company, say DEF, may decide XYZ's manufacturing prowess is worth having.

So what could DEF do? Buy XYZ. And, it would not even have to pay very much since corporations tend to trade at multiples of reported earnings.

The point of a hostile takeover is that the acquirer does not ask the acquiree if it wants to be acquired. It simply makes the acquiree's beleaguered shareholders an offer they will not refuse.

If that offer involves the ability to trade those dog-eared XYZ shares for some shiny, newly minted DEF shares, all the better. Why waste cash. Cash has to be earned first.

5 minutes later, a corporate restructuring is initiated. Skip ahead 60 more minutes and XYZ's previous CEO is on the sidewalk looking in and, as if by miracle, profit at DEF's new, XYZ division jumps 20%.

Fast forward another several weeks or perhaps a few months, the restructuring aimed at eliminating all remaining administrative redundancies is complete, and XYZ division profits settle at, miraculously, 60% of sales.

Then, since DEF's management had demonstrated its acumen for M&A, the next time it finds a suitable target, it will be able to count on shareholder support, at least for a while.

At many companies, the CEO's core talent is not running the business but finding and acquiring suitable targets.

On the one hand, this can create value for both customers and shareholders, as administrative overlap is relatively easy to remove. Likewise, sales, marketing and R&D can often be streamlined, integrated and made more efficient.

On the other hand, acquisitions, and especially the bootstrapping they can bring, can become so addictive that management cannot stop at only suitable targets, as any former WorldCom shareholder can certainly remember.

Not that this happens particularly often.

The more likely scenario, XYZ will restructure.

Sitting on a board of directors of a corporation is great work if you can get it. If XYZ is taken over, what use could the acquirer possibly have for the acquiree's board of directors?

This is when survival instinct kicks in.

Faced with impending doom, XYZ's board's independent members will hold an emergency meeting. 5 minutes later...

From an investor perspective, a restructuring is not as good as a takeover, but still better than nothing.

From the former CEO's perspective, same difference.

Note: assuming I was confident in my analysis, I would probably buy options to maximize profit even though the downside would be worse.

Problem is, getting to this information is tough.

Being bright, XYZ's management is aware that if investors find out… well, Dennis Kozlowski could give a firsthand account of what can happen, though I doubt he is in a talking mood.

So what can management do?

Magic wand.

A magic wand so potent it can turn a looter into an idiot.

A magic wand so unstoppable it keeps everyone at a distance, like an obviously drunk driver in the fast lane.

A magic wand so simple it takes only a few, well-placed adjustments.

So what is this magic wand?

Reclassification.

Management simply reports expenses that belong in administrative as cost of sales.

Cost of sales is a big number. Adding a little extra admin to it will only make it a bit bigger.

Better yet, it will make the company look like it is run by idiots, best avoided like the drunk in the fast lane.

Some time ago, I was riding my motorcycle in the fast lane (admittedly faster than allowed, but not by that much). Then I noticed headlights approaching at speed. At first, I began contemplating how I would explain my regrettable life choice to an officer of the law, but then those headlights seemed to be behaving erratically, as if they belonged to someone not proficient at operating a motor vehicle.

I changed lanes with haste.

Moments later, those headlights were in front of me, colliding first with one car, then another, then a third before flipping over several times. When it was over, to my surprise, no one died. Yes, the DUI was taken away by ambulance, but that was a good thing. I just hope he had a very long time behind some very strong bars to reflect on his really regrettable life choice.

The point is, whenever, as an investor, I notice a company that seems to be run in a less than proficient manner, I move out of the way. With haste. After all, being an observer to a corporate pileup is better than being a participant in one.

So, in this scenario, the manager can have their cake and keep their job too.

At least until an accountant with a conscience blows the whistle (or files suit, or resigns), an activist investor with the resources to dig deep digs deep, or a partner rotation brings some new skepticism.

Oddly enough, management also needs to be wary of an industry crisis. If everyone assumes the company will fail and it survives, it will certainly raise some eyebrows somewhere.

Well, except the widows and orphans who get stuck with the ABC stock in the retirement portfolio.

So, why does IFRS | US GAAP skip over the important to focus on the marginally relevant?

Technically, only IFRS completely ignores cost of sales, having no standard that addresses this issue.

The ASC does mention cost of sales. However, its level of indifference is comparable.

ASC 705-10-05-1A (edited): The Overall Subtopic only provides links to guidance on accounting for the cost of sales and services in other applicable Subtopics because the asset liability model used in the Codification generally results in the inclusion of that guidance in other Topics. ...

ASC 705-10-25-1 (edited): This Section consists solely of links to other Subtopics because the asset liability model used in the Codification requires that applicable guidance be included in other Topics. ...

ASC 705-10-45-1: Paragraph superseded by accounting Standards Update No. 2014-09.

ASC 705-10-45-2: Paragraph superseded by accounting Standards Update No. 2014-09.

ASC 705-10-45-3: Paragraph superseded by accounting Standards Update No. 2014-09.

ASC 705-10-45-4: Paragraph superseded by accounting Standards Update No. 2014-09.

ASC 705-10-45-5: Paragraph superseded by accounting Standards Update No. 2014-09.

Because IFRS | US GAAP is built on an asset/liability model.

Under asset/liability model, the guidance focuses on assets and liabilities. Revenue, expenses, gains and losses are relegated to mere changes in assets and liabilities. While it has been criticized and does lead to some counterintuitive guidance, this model has been the foundation for IFRS | US GAAP for some time with no change expected.

Interestingly, even though it is the foundation for the guidance, the ASC only mentions the asset/liability model in passing (ASC 705-10-05-1A) while IFRS does not mention it at all.

Why not? Perhaps because this model is much hated in the professional community (link, local link here link, local link), can lead to hard to interpret and confusing guidance, and is the exact opposite of the income/expense model managers, investors or governments would prefer accounting standards to be based on.

Perhaps, because if they don't talk about it, no one will notice.

Perhaps, because they are whistling past the graveyard.

Perhaps, because it is the right thing to do.

Perhaps, because they can.

Regardless, besides the one tiny slip in ASC 705-10-05-1A, nowhere do the standard setters state they base all their guidance on this much maligned model.

They just do.

Editorial note: while it may seem this page is being critical, it actually supports the asset/liability model even though it does cause confusing and counterintuitive guidance. The reason? To paraphrase Sir Winston, it is the worst possible model, except for all the others. This page also applauds the boards for sticking to their guns in the face of all the hate.

For example, IAS 12 | ASC 740 do not determine deferred income on the basis of income. Instead they determine it on the basis of the tax base of assets and liabilities.

Wait. What?

The tax base of assets and liabilities.

Why? Isn't income tax, as the name suggests, based on income?

Well, yes, it is. But the model used by the IASB | FASB to underpin their guidance requires that deferred tax be calculated the tax base of assets and liabilities, not by simply comparing financial income with taxable income.

Kind of like reaching over your head with your right hand to scratch your left ear.

Yes, exactly like that.

Hmmm. A bit silly. Don't you think?

Theoretically valid is theoretically valid. Stop winging and do with it.

OK

The formal shift from the income/expense model to the asset/liability model in US GAAP was relatively gradual. In 1978, the first FASB Conceptual Statement (SFAC 1) still reflected the income/expense model as the primary basis for financial reporting. However, by the time SFAC 6 was issued in 1985, the conceptual framework had shifted decisively to the asset/liability model. In IFRS, the transition occurred somewhat later. During the IASC's tenure, the income/expense model was prevalent. The transition to the IASB marked the clear shift.

These are broad generalizations, however. The asset/liability model influenced accounting practice well before this. For example, both the topic at hand (IAS 2 | ASC 330) has been firmly grounded in the asset/liability model since inception. Similarly, neither IAS nor IFRS has ever included explicit guidance on cost of sales, while US GAAP has provided guidance in this area it has always been rudimentary.

Importantly, the pursuit of theoretical correctness only constrains the standard setters.

So, while IASB | FASB have to politely ring the doorbell, the practitioner can simply let themselves in through the back door.

For example, a strict interpretation of the letter of IAS 2 | ASC 330 would require delivery costs to be capitalized to inventory. Assume a company acquires 400 items of merchandise and 20 different materials shipped in a single consignment. Per the letter of the guidance, it would need to allocate the shipping to each of those 420 items (true, software can do the heavy lifting, but that is not the point).

Conversely, it would simply expense the shipping through cost of sales (as a variable indirect cost, below) and call it a day.

Would the result be really so different that it would be a material misstatement?

Or, put colloquially, is the juice worth the squeeze.

In other words, does the cost associated with pedantically applying the letter of the guidance justify the benefit of reporting a result not materially different from a result that could be achieved by an alternative, less formalistic approach?

This, my friends, is an issue best resolved during an honest, after-hours exchange of opinions between the practitioner and the engagement partner. Assuming both are rational and reasonable professionals, assuming the amounts involved are not material the cost/benefit constraint provides both sides with ample flexibility to reach a mutually acceptable compromise.

So, if one can arrive at the same destination by either taking a tunnel or driving over a mountain, which makes more sense?

As a bonus, since financial statement users prefer the income/liability approach anyway: Win - Win.

Unfortunately, not all practitioners see it this way.

On the preparer side, practitioners generally prefer procedures requiring minimal effort, while achieving the intended objectives. On the auditor side, there is often a predilection for pedantic adherence to the strict wording of the guidance, even if it leads to irrationally complex, convoluted processes and results in unnecessarily bloated administrative budgets.

Fortunately the cure for this malady is readily available over the counter, and can be administered orally.

Whenever an auditor insists on a cumbersome procedure simply because it is outlined in the guidance, the practitioner may push back by reminding that IFRS | US GAAP aims to address reporting and disclosure requirements, and that any particular procedure is merely a means to that end.

The practitioner can also point out management has flexibility to design internal processes, provided they yield results materially consistent with the aims of the standards. How they achieve this result is less than relevant.

The practitioner can also point out that while auditors have the power to issue qualified opinions, they must justify such opinions not by simply showing how an entity's preferred procedure differs from the procedure outlined in the guidance, but by demonstrating how that difference causes a material misstatement in the financial statements and related disclosures. Barring that, they would need to explain how the additional cost of their preferred treatment justifies the increased administrative burden while only yielding an immaterially different result.

Being rational, when faced with informed and reasonable client resistance, most auditors recognize that insisting on a pedantic application of the letter of the guidance is unjustifiable and adjust their approach accordingly.

Note: the above only applies in an IFRS | US GAAP context. In a national GAAP context, some statutory standard, including many of the national GAAPs drafted as dictated by the EU accounting directive, do prescribe procedures and not adhering to such procedure is subject to criminal sanctions often including, but not limited to, incarceration.

IAS 2 | ASC 330 also shows accounting guidance can be succinct.

Glancing over the guidance on inventory, the image that comes to mind: a ladybug riding a water buffalo.

Printed out, ASC 330 is barely two pages (double spaced). While not as concise, IAS 2 is a pamphlet, not a novel.

Juxtaposed against the labyrinthine and multifaceted pronouncements governing investments, derivative instruments, or fair value measurement, or perplexing and counterintuitive guidance pertaining to deferred tax, girth and mind-numbing complexity makes even the seasoned practitioners shiver with dread, IAS 2 | ASC 330 are like a ray of sunshine on an otherwise cloudy day. That is until one realizes that terse pronouncements necessitate substantial interpretative evaluation.

For instance, the exclusionary provisions articulate that "Other items such as abnormal freight, handling costs, and amounts of wasted materials (spoilage) require treatment as current period charges rather than as a portion of the inventory cost." This terse directive lacks definitional clarity regarding the term "abnormal," omits a prescriptive criterion delineating "abnormal" from "normal," and fails, perhaps most frustratingly, to elucidate the appropriate categorization for said costs beyond dictating their exclusion from inventory valuation. Consequently, ambiguity persists as to whether such costs may be presented as a sub-classification of cost of sales, presented utilizing a mezzanine reporting scheme between cost of sales and gross profit, subsumed by selling or distribution, aggregated with administrative or perhaps general expense, presented in the obtuse other expense section or simply reported as a loss, ambiguity which must be surmounted by a copious application of professional evaluative reasoning and a not insignificant quantity of prudent discernment.

Thus, in the absence of detailed and prescriptive procedural guidance, practitioners must remain cognizant that informed discretionary assessment must be applied and supported, especially when the assessment must be justified to often skeptical audit or regulatory professionals, or perhaps judicial authorities if the issue escalates sufficiently.

Thus unfolds the inherently difficult and complex cognitive landscape necessitated by principles-based guidance, which purposefully eschews detailed and prescriptive criteria which, by eliminating procedural ambiguity, may serve as a perceptual prosthesis for practitioners who preference unequivocal and prescriptive governance protocols that, while constricting autonomous prerogative, do ameliorate the hazard inherent in formulating and justifying unmandated accounting policy.

Obviously, we jest, but brevity does have a downside.

Why so terse? It harks back to a simpler time, when standard setters assumed judgment could fill in the details.

Keeping track of items acquired with the intent to re-sell has been necessary since long before Luca Pacioli made his contribution to our profession. So, when the Committee on accounting Procedure penned the first Accounting Research Bulletin, they had a rich history to draw on and simply assumed, since everyone already knew how to account for inventory, a few words would be sufficient. When the FASB took over, they assumed, since everyone already knew how to account for inventory, those few words would be sufficient, so just carried them forward.

IAS 2.8 specifies that inventories are goods purchased and held for resale. ASC 330-20 goes a step further emphasizing, to be recognized and reported as inventory, an item must have been originally acquired with the intent to resell.

ASC 330-20 (edited) states: ...[the] definition of inventories excludes long-term assets subject to depreciation accounting , or goods which, when put into use, will be so classified. The fact that a depreciable asset is retired from regular use and held for sale does not indicate that the item should be classified as part of the inventory...

Put simply, an asset originally acquired for use not sale may not ever be classified as inventory, even if the entity decides to sell it.

This implies, for example, spare parts acquired to be consumed while providing services are classified as inventory, while spare parts held for repairing machinery or equipment are not, despite both often being called "spare parts inventory."

This interpretation is further reinforced by IAS 16.8, which was added to address previous misinterpretations and misuse of the term "spare parts inventory."

Similarly, if an entity constructs buildings for resale to any customer, they are inventory, subject to IAS 2 | ASC 330. But if it constructs them for its own use, they are PP&E subject to IAS 16 | ASC 360, while if it constructs them for a particular customer, they are projects (contract assets) subject to IFRS 15 | ASC 606.

On completion, the entity would cease applying IAS 2 and begin applying IAS 40.

Note: as US GAAP does not allow the remeasurement of non-financial assets (except industrial or agricultural commodities subject to ASC 330-10-35-16) to fair value, it has no counterpart to IAS 40 whose key requirement is that fair value of investment property must always be determined so it can be either disclosed or reported.

As it started drafting standards a half-century later, the IASC did add a few extra words, but not that many. When the IASB took over, they assumed, since everyone already knew how to account for inventory, those few extra words would be sufficient, so just carried them forward.

Note: true, the FASB did revisit the accounting for inventory, back when converging with US GAAP and IFRS was still on the agenda, but it only added a paragraph or so, then called it a day.

While a welcome respite from sheer mass of recent pronouncements, this brevity is a double-edged sword

The downside of succinct guidance is, well, it is succinct.

For example, IAS 2 | ASC 330 prohibits abnormal freight, handling and wasted material from being recognized as inventory but fails to provide any criteria for distinguishing "abnormal" from "normal." Similarly, beyond prohibiting the inclusion of "abnormal" items in inventory, it does not provide any guidance on how abnormal items are to be treated. May they simply bypass inventory but be included in cost of sales? May they bypass cost of sales and be reported in the mezzanine between cost of sales and gross profit? Should they be reported as sales or distribution expenses? Should they be included in administrative expenses or general expenses or other expenses? May they be simply written off as losses?

The guidance does not specify.

So, how does the practitioner determine what abnormal is and what should be done with it?

Judgment.

Judgment will be second-guessed. First by management. Then by auditors. Then by regulators. Then, if the issue escalates sufficiently, at court and, if one is extremely unlucky, by jury comprising a cross-section of the general population who would probably not recognize judgment if it kicked them in the shins.

So, welcome to the joy ride that is principles-based guidance. Don't forget to fasten your seat belts.

Inventory comprises:

- Merchandise

- Material

- It becomes part of the product being produced.

It is consumed by the production process.

- Products

- Direct costs

- Direct material

- Direct labor

- Indirect costs (manufacturing overhead)

- Fixed

- Variable

- Services

Merchandise is any item acquired for resale without modification.

While minor modifications, such as dealer-installed options in automobiles, may occur, merchandise is generally sold in the same condition in which it was bought.

The primary value added by the retailer or distributor lies in logistics and market access: relocating merchandise to a suitable sale point, locating potential buyers, facilitating transactions, and above all, providing a satisfying buying experience.

Consequently, the accounting for merchandise goes from simple and even simpler.

For entities that have invested in automation such as barcode, QR code or RFID tag scanners, the MIS takes care of itself, with practically no human involvement necessary.

For entities that prefer the old school, hands-on method, adding beginning inventory to purchases and subtract ending inventory cannot be considered challenging accounting.

True, a physical inventory needs to be taken at least once per period, but that is someone else's job.

The accounting for material is thus simple. When acquired merchandise is recognized with a debit to inventory / credit to a cost (cash, accounts payable, etc.). When control passes to the customer, merchandise is derecognized with a debit to cost of goods sold / credit to inventory.

Like merchandise, material is acquired to be re-sold.

Unlike merchandise, it must be converted into or added to a product first.

US GAAP has been recently updated (ASC 220-40-50-6) introducing the term "purchases of inventory."

This item comprises raw material and merchandise if taken together. However, if an entity engages solely in manufacturing, it would continue to use the raw materials/direct material labels. Similarly, a retailer would continue to refer to its inventory as merchandise. While an entity that does both could use a "purchases of inventory" label in its reports, such an entity would likely report its cost of products sold separately from its cost of merchandise sold. So, in practice, "purchases of inventory" is neither an appropriate accounting title nor financial statement line item. It is simply the term the standard setter uses to refer to material and merchandise with a single descriptor.

Note: IAS 1 and IFRS 18 refer to "raw material" expense as a component of cost of sales. It is also uncommon for entities reporting under IFRS to disaggregate cost of sales into detailed component parts for presentation or disclosure purposes. While materiality can overcome this practice, a detailed breakdown of cost of goods sold is fairly rare in the IFRS context.

Also note: materials or supplies consumed during the manufacturing process would also fall into the "purchases of inventory" | "raw material" categories. However, good practice is recognizing these items as production supplies and reporting them in the manufacturing overhead (indirect costs) component of cost of sales (if cost of goods sold is reported on a disaggregated basis).

Material falls into two general categories:

Unlike raw material, production supplies do not become a physical part of products. Instead, they are consumed during the manufacturing process.

From an accounting perspective, while they are rarely material enough to be reported as a separate balance sheet line item, when a product is sold, production supplies are included in cost of sales as variable indirect costs (production overhead), separate from material. This distinction is important when cost of sales is reported in granular detail.

Production supplies generally comprise consumables, such as lubricants, and often small parts like fasteners, capacitors, or resistors. The key accounting difference between a raw material and a production supply is that manufacturers typically track raw material through production, recognizing it first as raw material, then in work in process, and later in finished goods. Finally, when the finished goods are sold and revenue recognized, the raw material is derecognized from the balance sheet and recognized on the profit and loss | income statement as part of cost of sales. Production supplies, in contrast, generally bypass these intermediate steps, moving directly from inventory to cost of sales as they are consumed.

This also means the definition of production supplies is entity-specific. While many companies may calculate their screw expense by simply summing a period's screw purchases (making sure to subtract beginning screw inventory and add back ending screw inventory), others may meticulously track every single screw, especially if those screws involve expensive materials, specialized tooling, and highly skilled workers.

At the other end of the spectrum, some companies treat low-value (a.k.a. small assets) like production supplies. While it is fairly common to expense wrenches or spanners as if they were screws, some companies will apply the same policy to any asset costing less than $5,000 even if that asset is a portable drill press or PC.

National GAAPs, particularly if they are legalistic, set explicit monetary limits for asset capitalization. While neither IFRS nor US GAAP set such limits, this issue did come up during the deliberation process of IFRS 16 | ASC 842 where the boards addressed the staff's concerns regarding "small assets," the way many national GAAP refer to low-value items.

This issue was considered sufficiently important that the IASB decided to include a low-value (small) asset exception in IFRS 16. While the standard itself does not provide a quantification, in the basis for conclusions $5,000 was mentioned as a reasonable threshold.

As this is the only guidance that provides a similar quantification, even though it cannot be considered authoritative, it has become the basis for common practice when evaluating (by analogy) any "small asset."

Since ASC 842 does not include a 'small asset' exception similar to IFRS 16, analogizing from ASC 842 is not an option under its guidance. Nevertheless, since the ASC 842 Basis for Conclusions mentions the same $5,000, $5,000 is commonly used as a rule of thumb for "small" in US GAAP as well.

Thus, when applying this guidance, a company would need to test whether its aggregate "small assets" (not just those acquired in the accounting period but) do not cross a materiality threshold. If, for example, it can be reasonably assumed the company actually has "small assets" exceeding 1% of total assets, some of those assets will need to be capitalized to make sure that no material misstatement is being made.

Note: the same test would also need to be performed in IFRS because the $5,000 threshold only applies to small assets being leased, not small assets in general.

Thus, while not widely used common practice, this guidance is used to justify expensing items, such as personal computers or light machinery and equipment such as compressors, welders, portable drill presses, provided the per item cost does not exceed 5,000 USD. This issue is discussed in more detail in the Consumables (small, low-value assets) section of this page and Small assets section of this page.

As the guidance provided by IAS 2 | ASC 330 is rudimentary, it leaves significant room for professional judgment, and imagination, to be applied.

However, the accounting for material is equally as simple as the accounting for merchandise.

Technically, strict adherence to the guidance would result in a different. Rather than being derecognized with a debit to cost of goods sold, it would be derecognized with a debit to WIP. However, as running costs through inventory can be more work than it is worth, simply expensing it as it is consumed (perpetual method) or once per period (periodic method) is usually close enough. A more detailed discussion of why it is usually good enough is provided above.

The accounting for products is somewhat more involved than the accounting for merchandise and material.

The default method of accounting for production is full absorption costing.

While IAS 2 | ASC 330 does not use the term "full absorption costing" but does require it. Specifically:

Black letter IAS 2.23 states: The cost of inventories of items that are not ordinarily interchangeable and goods or services produced and segregated for specific projects shall be assigned by using specific identification of their individual costs.

While similar, ASC 330-10-30-10 is not nearly as categorical stating (edited): ... While in some lines of business specific lots are clearly identified from the time of purchase through the time of sale and are costed on this basis, ordinarily the identity of goods is lost between the time of acquisition and the time of sale.

Nevertheless, under both, if an entity is capable of clearly identifying inventory costs as a product moves from raw material to finished good, it shall do so, reinforcing full absorption costing as the default accounting method.

However, given the practical difficulties of applying this method in the real world, particularly in serial manufacturing, both IFRS | US GAAP (specifically IAS 2.21 | ASC 330-10-30-12) explicitly allows standard costing, which is considerably simpler from an accounting methodology perspective. Similarly, IAS 2.21 | ASC 330-10-30-13 allows retailers to use a simplified, retail method.

In practice, entities often use other methods not explicitly mentioned in or allowed by the guidance. A good example is direct costing but various other hybrid methods are also used.

Direct costing is a common, internal method not generally appropriate for IFRS | US GAAP reporting purposes. However, if adjustments reflecting indirect costs are made, it could be used. As these adjustments need only be made periodically, it would be considerably simpler than tracking these costs as products move through the manufacturing process.

Examples include activity-based costing (ABC), throughput accounting, marginal costing, lean accounting , resource consumption accounting (RCA), target costing, etc.

However, for any method to be acceptable from an IFRS | US GAAP perspective, the result must be consistent with full absorption costing, ensuring that reported cost of sales includes direct material, direct labor and indirect production costs, both fixed and variable.

The costs fully absorbed to inventory comprise:

In US GAAP financial reports, a granular breakdown of cost of sales (cost of goods sold if only products are involved) in the footnotes is required.

ASC 220-40-55-11 includes the following illustration of how to apply ASC 220.

As this example clearly illustrates, the guidance requires a granular disclosure of various expense components. For example, a disaggregation of cost of goods sold is required (from December 16, 2026).

This reporting approach is less common in IFRS. Nevertheless, if the individual components of cost of sales are material, an auditor may require this granular information due to Practice statement 2.

However, PS 2.4 states: The Practice Statement provides non‑mandatory guidance; therefore, its application is not required to state compliance with IFRS Standards.

This implies that an auditor cannot insist on a granular breakdown of cost of goods sold, or any larger expense item, if a standard or interpretation does not require it, which neither does.

Material out of which a product is manufactured or that becomes a physical part of a product.

Direct material is what becomes of raw material when it moves from inventory to cost of goods sold.

Employee benefits accruing to employees directly involved in the production of product (rendering of services: below).

These typically include wages and costs such as overtime, social security taxes, health insurance, safety and hazard insurance, meals, clothing, work aids, etc. They may not, however, include any employee benefits for any activity besides production as discussed in the excluded items section further down this page.

Commonly, depreciation, amortization and rent. Fixed costs may also include, for example, royalty payments, supervisor salaries and other costs that do not change with production volume.

Note: costs do not need to be linear to be fixed. For example, depreciation determined using a diminishing balance method would be a fixed cost even though it is not a straight line expense. The key distinction between fixed and variable costs is that the former are not correlated with production volume while the latter are.

Variable costs change together with production volume. The correlation need not be exact, but it must exist. If it does not, they the costs are fixed, not variable.

variable costs most often comprise factory (production) supplies, consumables (small tools not capitalized), repairs and maintenance (MRO), quality control and inspection, utilities (electricity, fuel, water, sewage, waste removal, etc.) or setup and re-tooling.

As outlined in IFRS 18.80 | ASC 220-40-50-6, an entity should recognize "raw material" | "purchases of inventory," which generally includes materials or supplies consumed during the manufacturing process. Nevertheless, it is good practice to classify material consumed in the production process as manufacturing overhead (indirect costs) instead of including it in direct material.

While this distinction is not explicitly mandated by IFRS | US GAAP, it is widely accepted and appropriate for accurate cost allocation and reporting.

Some entities treat low-value (also known as small) assets like production supplies, expensing them as they are acquired. This practice is particularly common in jurisdictions where national GAAP sets explicit monetary limits for asset capitalization. While neither IFRS nor US GAAP sets explicit universal thresholds for capitalization, the concept of "low-value" assets was discussed during the development of IFRS 16 | ASC 842, with a value of approximately $5,000 cited as a practical benchmark in the Basis for Conclusions of both standards. Although this amount is not a formal capitalization limit under either framework, it has become a widely accepted practical threshold when making capitalization versus expense judgments.

This site does not recommend expensing assets solely based on acquisition value. Instead, it recommends capitalizing such low-value assets using group or composite depreciation methods, as discussed on this page.

Quality control generally refers to the overall process of ensuring that products meet quality standards, while quality inspection specifically involves examining products or processes to detect defects. Both activities are typically classified as indirect production costs.

As a rule, setup and tooling costs are included in the acquisition cost of the item(s) of PP&E when those items are initially recognized. Once such item(s) have been initially set up, any subsequent setup and retooling costs cannot be capitalized to PP&E but should instead be capitalized to inventory and allocated to the related production run.

Depending on how production is organized and personnel compensated, they may or may not include costs such as supervisor or production manager salaries. However, regardless of their composition, care must be taken that variable costs never include any of the excluded items discussed further down this page.

As such, this page addresses both the accounting for receivables and revenue recognition simultaneously.

With respect to revenue recognition, the two key issues are timing and amount.

Both of these are discussed on this page.

However, as the timing of revenue recognition coincides with the timing of inventory derecognition, an additional discussion of this issue is provided on the inventory page.

Including services on this list always raises eyebrows. But it does have, albeit tenuous, support in the guidance.

IAS 2.6.c (edited, emphasis added): Inventories are assets: ... in the form of materials or supplies to be consumed in the production process or in the rendering of services | c To be currently consumed in the production of goods or services to be available for sale.

ASC 330.20.c states: Inventory: The aggregate of those items of tangible personal property ... c To be currently consumed in the production of goods or services to be available for sale.

While this IAS 2 specifically refers to materials or supplies IFRS 15.91 to 98 specify that both incremental costs of obtaining a contract and costs to fulfill a contract must be capitalized. This guidance applies all entities manufacturers and service providers alike.

Similarly, those ASC 330 specifically discusses items of tangible personal property, ASC 606-10-15-5 mentions and ASC 340-40-25-1 to 8 provides comparable guidance.

Given that revenue guidance is considerably more modern than inventory guidance, a more flexible interpretation of the latter is justified.

More importantly, the argument that accrued service costs may not be included in inventory because services lack physical substance misses the point.

As discussed above, inventory is not the point. Cost of sales is the point.

Put less simply, giving due consideration to the materiality constraint, coupled with the incontrovertible fact that all costs related to the provision of services are ultimately subsumed within cost of sales, service providers may, with a degree of justifiable latitude, elect to construe the antiquated and arguably obsolete guidance pertaining to inventory through the interpretative prism afforded by the contemporaneously updated revenue recognition standard, namely IFRS 15 | ASC 606. Determined by analogy, the policy of capitalizing all costs directly related to revenue into a single asset item—rather than dispersing them among various disjointed assets—thereby eschewing the historically arbitrary bifurcation predicated upon the archaic goods versus services dichotomy, the abrogation of which constituted one of the principal objectives of the comprehensive project culminating in the issuance of IFRS 15 | ASC 606, a standard promulgated expressly as a wholesale replacement for IAS 18 | ASC 605, rather than as a mere incremental amendment, reflecting the broader recognition that antiquated accounting infrastructure frequently necessitates wholesale demolition and replacement, not mere cosmetic renovation or superficial rebranding, would be justifiable.

Be that as it may, the juice is probably not worth the squeeze?

While the above argument should be sufficient to convince even the most pedantically inclined auditor to accept the policy, is it worth the effort?

As a general rule, practitioners only have so many matches. Is it worth burning one just to prove a point?

Put another way, is tilting against the pedantic predilection to apply irrational and outdated guidance verbatim worth the time and, since auditors often bill by the hour, expense?

As a wise man once said: Más vale buen acuerdo que buen juicio.

So if the auditor balks at including accrued service costs in inventory and would rather see them recognized as accruals, why not make them happy and acquiesce?

Note: the above only applies to basic, point-of-time services or those measured cost-plus. More complex services, accounted for as projects, fall into the contract asset category outlined in IFRS 15 | ASC 606. A more detailed discussion of this issue is provided in the Percentage of completion (over time) section of this page.

On the balance sheet inventory is classified:

- Merchandise

While the cost of merchandise is always capitalized, the costs associated acquiring merchandise (locating sellers, shipping, handling, storage, etc.) are often expensed (as cost of goods sold) as incurred, even though this policy would not be consistent with the letter of the guidance (as discussed above).

While neither the IASB nor FASB XBRL taxonomy considers merchandise sufficiently material to be included on a standard balance sheet, both include it in the footnotes as Merchandise and RetailRelatedInventoryMerchandise respectively.

Since merchandise is specifically mentioned in the guidance (IAS 2.8 and 37 | ASC 330-20), if it represents 5% or more of total assets, it would need to be presented as a separate, balance sheet line item. A supplement discussion on how to determine materiality is provided on this page.

As the accounting for merchandise is practically indistinguishable from the accounting for raw material, the two are often reported as a single line item even though they would be recognized in separate COA accounts.

- Raw material

While the cost of raw material is always capitalized, the costs associated acquiring raw material (locating sellers, shipping, handling, storage, etc.) are often expensed (as cost of goods sold) as incurred, even though this policy would not be consistent with the letter of the guidance (as discussed above).

While the FASB XBRL taxonomy considers raw material sufficiently important to be included as in item on a standard balance sheet (InventoryRawMaterialsAndSupplies) and reported in the footnotes (InventoryRawMaterials), IASB XBRL only reports it in the footnotes (RawMaterials).

Since material is specifically mentioned in the guidance (IAS 2.8 and 37 | ASC 330-20), if it represents 5% or more of total assets, it would need to be presented as a separate, balance sheet line item under both IFRS | US GAAP. A supplement discussion on how to determine materiality is provided on this (page).

As the accounting for raw material is practically indistinguishable from the accounting for merchandise, the two are often reported as a single line item even though they would be recognized in separate COA accounts.

Raw material transforms into the direct material component of cost of goods sold when finished goods are transferred to a customer. An additional discussion of this issue is included in the following sub-section.

- WIP

- Finished goods

The balance sheet recognition of merchandise generally aligns with the description of merchandise (above).

However, additional points need to be made:

The balance sheet recognition of raw material generally aligns with the description of material (above).

However, additional points need to be made:

ASC 220-40-55-11 illustrates how the guidance provided by ASC 220 would be applied to various income statement items. Although an illustration, unlike IFRS where illustrations are not considered core guidance, the ASC makes no distinction between illustrations and its remaining guidance. This implies that the disaggregation outlined below is mandatory. What is not, however, mandatory are the exact line ites that will comprise the disaggregation. Obviously, as each entity will have different material expenses or groups of expenses, a one size fits all list is not possible. Which is also the reason the guidanc is presented as an illustration rather than a comprehensive list.

IFRS provides no specific guidance requiring a detailed level of disaggregation similar to that found in ASC 220-40-55-11. Nevertheless, since all material items must be disclosed as outlined in IFRS Practice Statement 2, auditors may require comparable disaggregation. Auditors also have the authority to issue a qualified opinion if material disclosures are omitted.

Note: research conducted by the author of this page for an auditor client indicated that this level of granular disclosure is relatively rare among entities subject to EC 1606/2002. This observation suggests inconsistency in how auditors interpret and apply IFRS Practice Statement 2 in the EU context.

Also note: the engagement mentioned in the previous note did not require a statistically representative sample nor academic rigor. Therefore, the conclusions presented here should not be given the credence reserved for peer-reviewed research. Specifically, readers of this page are advised to either repeat the research for themselves or seek out peer-reviewed research.

Interestingly, ASC 330 uses the term work in process, which accurately describes the manufacturing process of transforming raw materials and supplies into finished products.

In contrast, IAS 2 uses work in progress, which more suitably describes the progress a building makes from foundations to finished structure.

In practice, the acronym WIP solves the problem with little fuss.

At the risk of belaboring the point, a small subset of practitioners delight in often gratuitously nuanced disputations regarding the precise semantic fidelity and philological exactitude of arcane and highly specialized terminological constructs, particularly when interacting with similarly inclined cohorts who manifest an almost compulsive fixation upon the literal and verbatim phraseology enshrined within extant authoritative guidance. There concurrently exists a divergent faction of professionals who consciously eschew such lexical fastidiousness in favor of concentrating their intellectual and practical energies upon matters of substantive import and pragmatic consequence.

The former argue about whether to call it work in process or work in progress. The latter simply say WIP.

The term finished goods is self-explanatory. It denotes goods that are finished.

On the profit and loss statement inventory becomes:

Previously just good practice, US GAAP requires a granular breakdown of cost of sales .

Reinforcing previous best practice, from 12/16/2026 ASC 220-40-55-11 mandates a disaggregation of expenses consistent with the following illustration:

IFRS, in contrast, does not provide specific guidance on the level of disaggregation required.

As a general rule, a line item is disaggregated if its constituent parts can be separately recognized and are material.

For example, if an entity only sells merchandise, it would only report a single cost of merchandise sold line item even if merchandise represented 70% of total expenses.

In contrast, if the entity sold products, it should disaggregate cost of sales and report, for example, direct material, direct wages, depreciation and other production overhead.

However, IFRS does not mandate the detailed disaggregation required by US GAAP (above).

Instead, materiality, as defined in IFRS 18 (A), guides overall presentation while additional guidance on making materiality assessments, including decisions about disaggregation, is found in practice statement 2.

However, PS 2.4 states: the Practice Statement provides non-mandatory guidance; therefore, its application is not required to state compliance with IFRS Standards. Consequently, auditors may recommend disaggregation based on materiality considerations, but cannot insist on it unless a specific standard or interpretation explicitly requires it.

Thus, unlike under US GAAP, IFRS entities often present considerably less granular cost breakdowns. Reflecting this, the IASB XBRL taxonomy does not include detailed cost components such as direct material (CostDirectMaterial), direct labor (CostDirectLabor) and overhead (CostOfGoodsAndServicesSoldOverhead), like the FASB taxonomy. Interestingly, it does include the cost of merchandise sold item (CostOfMerchandiseSold), even though it omits the broader cost of goods sold item.

- Direct material

- Direct labor

- Indirect production costs (overhead)

Employee benefits | wages accrued to workers engaging in production activity.

This issue is discussed in direct labor subsection above.

In an IFRS or US GAAP context, overhead is generally taken as a synonym for indirect production costs and comprises costs such as depreciation of manufacturing facilities or electricity consumed by production machinery.

In a national GAAP context, it is occasionally an arbitrarily determined portion of administrative or general expenses classified as cost of sales at management discretion. While it may be possible to justify allocating some or a portion of some, for example, managerial salaries to production overhead, care must be taken so the guidance provided by IAS 2.16.c | ASC 330-10-30-8 properly and rigorously applied. This is especially important if an international subsidiary primarily applies local GAAP and only makes adjustments to arrive at an IFRS | US GAAP reporting package for its parent.

ASC 330-10-30-8 provides clear and succinct guidance stating (edited): ...under most circumstances, general and administrative expenses shall be included as period charges, except for the portion of such expenses that may be clearly related to production and thus constitute a part of inventory costs (product charges)...

While marginally less direct, IAS 2.16 does specify that administrative overheads that do not contribute to bringing inventories to their present location and condition are excluded from inventory and expensed in the period.

Inventory excludes:

- Administrative and general expenses

- Selling (distribution) expenses

- Double freight

- Rehandling

- Abnormal waste

- Idle or underutilized or production capacity

As outlined in IAS 2.16.c | ASC 330-10-30-8, administrative expenses may not be included in inventory or, more importantly (above), cost of sales.

Also discussed above, the brevity of the guidance means it limits itself to a simple prohibition without outlining any criteria to be used to distinguish costs that may be included versus costs that may not.

Using employee benefits as a proxy, the conservative approach would be to include only wages paid to production workers. This guarantees that only costs clearly associated with production are included.

Next most conservative: including direct wages and supervisor salaries. As work and the supervision of work are inseparable, this is the most common and best approach.

While not particularly popular with management, auditors love this approach.

In contrast, any attempts to include any management compensation will raise eyebrows.

Specifically, to paraphrase ASC 330-10-30-1, is the compensation paid to this member of management directly or indirectly necessary in bringing an article of inventory to its existing condition and location? Are you sure it is?

To quote ASC 330-10-30-8: Also, under most circumstances, general and administrative expenses shall be included as period charges, except for the portion of such expenses that may be clearly related to production and thus constitute a part of inventory costs (product charges).

Are you really sure this compensation qualifies as an exception to this general rule? Are you prepared to prove this compensation qualifies as an exception to this general rule? Are you sure you are not risking a qualified audit opinion just to make management happy? Really, really?

Well then, OK, go ahead.

While comparable, in a seeming role reversal, IFRS is stricter. Instead of being couched as a discussion of a principle, the guidance is a rule:

Black IAS 2.10 (emphasis added) states: the cost of inventories shall comprise all costs of purchase, costs of conversion and other costs incurred in bringing the inventories to their present location and condition.

Grey IAS 2.16 (edited) clarifies: ... excluded from the cost of inventories ... c) administrative overheads that do not contribute to bringing inventories to their present location and condition.

More adventurously: production manager salaries could be included. However, auditor skepticism should be anticipated and sufficient documentation to justify this policy prepared and presented.

The pinnacle: not only intermediate management but the plant manager is included. However, as one ascends the hierarchy, the higher a manager the broader his or her responsibilities, which makes both the justification and bifurcation more onerous. While tools such as the IDI Time Bank can aid the process, but auditors will invariably scrutinize any allocation scheme to ensure that only costs demonstrably associated with production-related tasks are recognized. Developing documentation that provides auditors with irrefutable evidence that the chosen policy complies with both the letter and spirit of IAS 2.16.c and ASC 330-10-30-8 is often so onerous, many entities simply desist.

With the complexities of management compensation duly addressed, applying the same to the remaining costs becomes markedly more straightforward. For example, the fuel, depreciation or repairs associated with a vehicle used to both will-call materials and deliver finished goods would be determined and bifurcated, the former could be capitalized to inventory (or simply expensed, above, to cost of sales) while the latter expensed as selling or distribution.

As outlined in IAS 2.16.d | ASC 330-10-30-8, distribution | selling expenses may not be included in the cost of inventory or, more importantly (above), cost of sales.

Also discussed above, the brevity of the guidance means it limits itself to a simple prohibition, without outlining any criteria to be used to distinguish costs that may be included versus costs that may not.

Fortunately, put colloquially, interpreting this guidance is a no-brainer.

No accountant would ever consider including, for example, salespersons' commissions, distributor rebates, trade show costs, travel, entertainment, or any demonstrably selling expenses in either inventory or cost of sales.

When it comes to distribution or selling costs tied to delivery or shipping, the distinction becomes less clear-cut. But, fortunately, double freight and rehandling have their own, stand-alone guidance.

While not explicitly mentioned by the guidance, double freight is commonly understood to mean the cost of shipping goods to a customer.

IAS 2.11 provides the more understandable guidance stating (edited): the costs of purchase of inventories comprise ... transport, handling and other costs directly attributable to the acquisition of finished goods, materials and services.

While it does suggest services may need to be shipped (perhaps by truck or train), the guidance makes clear that double freight, as it is not directly attributable to the acquisition of finished goods or materials but rather their sale, cannot be included.

In contrast, ASC 330-10-30-7 only discusses abnormal freight and handling costs. Nevertheless, ASC 330-10-30-1 also discusses expenditures or charges directly or indirectly incurred in bringing an article to its existing condition and location, so the guidance is comparable.

The result of applying each guidance is thus comparable: double freight is a selling or distribution expenses and may not be capitalized to inventory or, more importantly (above), expensed through cost of sales.

Like double freight (above), rehandling is a term commonly used in practice rather than by the guidance.

In IFRS rehandling falls under both the general guidance provided by IAS 2.11 and the specific guidance provided by IAS 2.16.b.

In US GAAP, it is not specifically addressed, but falls under same (ASC 330-10-30-7 and ASC 330-10-30-1 ) guidance as double freight.

However, this is just a formality and has no palpable influence on the accounting so it would be treated the same under both sets of guidance.

In general, two types of rehandling occur.

In the first type, a retailer first acquires merchandise from its manufacturer then ships it to a central distribution center, then a regional distribution center, then a local warehouse and finally a retail outlet.

Only the first cost, acquiring the merchandise, would qualify as inventory, or more importantly (above), cost of sales. The remaining costs, transportation, warehouse depreciation (or rent), warehouse staff, etc., are associated with the distribution channel, so recognized as distribution or selling expenses, even if substantial.

In the second type, a manufacturer first acquires material from its producer in country A then ships it to country B where some production steps are taken. It then ships the WIP to country C, where production is finalized. It then ships the finished goods, in bulk, to country D where the finished goods are packaged so they can be offered for sale in country D's language.

As with merchandise, the initial cost is included in inventory or cost of sales. So is the cost of shipping from A to B, and B to C. However, the cost from C to D is expensed. On the basis of what criterion?

The two most commonly used criteria are physical functionality and intended-use.

If the first is applied, the accountant determines where the product becomes physically capable of serving its purpose.

As the packaging in country D has no effect on physical functionality, and is merely done to facilitate the product's sale, the C to D leg is a selling or distribution expense.

However, what if the product produced in C were a television?

It may be possible to mail a memory card in an envelope. However, if a TV is shipped with protective packaging, it will have physical functionality only at the beginning of its journey.

Thus, in this situation, the repackaging is essential to maintaining physical functionality so the C to D leg would be included in inventory or cost of sales.

The question is, why would any accountant, if not an expert on assessing physical functionality, apply this criterion?

In another example, the item produced at C was a car door. This door could either be shipped to country D where production would continue to finished automobile. It could also be shipped to country E, where it would replace a door damaged in a collision.

In this, recognition takes care of itself: the cost of shipping WIP falls into inventory or cost of sales, while the cost of shipping finished goods is a selling or distribution expense. Simple.

Besides requiring no judgment, the intent criterion carries the added benefit of being fully consistent with the logic behind IFRS | US GAAP, even if it leaves some accountants, especially those just starting out with IFRS | US GAAP, shaking their head in disbelief.

IFRS | US GAAP focus on the financial. IFRS even goes so far as to include this word in its title.

In contrast, many national GAAPs focus on the physical. For example, many have an additional "semi-finished goods" inventory category that reflects this perspective.

Specifically, these GAAPs draw a distinction between partially manufactured goods and fully manufactured items. For example, an electric motor would be a semi-finished good, while the washing machine, once the motor (and all the other semi-finished goods) was installed, would be the finished product.

This reflects the assumptions that are the foundation for the guidance.

Under the labor theory of value, economic value is created by combining labor and material with the help of physical capital.

Under the exchange theory of value, economic value is created not by creating a physical thing but by creating something someone wants to buy.

Under the labor theory of value, the distinction between partially created value and fully created value has to be given accounting recognition during the production process.

Under the exchange theory of value, this is irrelevant because no value is created until the moment of sale.

Unfortunately, theory can also influence behavior.

For example, in accounting based on the labor theory, a change in inventory is recognized by debiting inventory/crediting revenue.

This may, and has, led careless managers to assume they are creating value even though they are only producing goods no one will ever buy.

It can also lead to warehouses full of unwanted goods lingering for years, even decades, because, since physical existence has value, testing for net realizable value has no economic foundation.

Under the labor theory of value, accountants also have to examine, for example, where in the production process a product achieves its physical functionality after which no additional value can be added.

In contrast, under the exchange theory of value, the only issue an accountant has to consider is whether the cost was associated with the exchange or not.

To accountants moving from a national GAAP environment to IFRS | US GAAP, it may seem as if something is missing.

It is not. It really is that simple.

As outlined in IAS 2.16.a | ASC 330-10-30-7, abnormal amounts of wasted materials (also known as wastage, spoilage or shrinkage) may not be included in the cost of inventory or, more importantly (above), cost of sales.