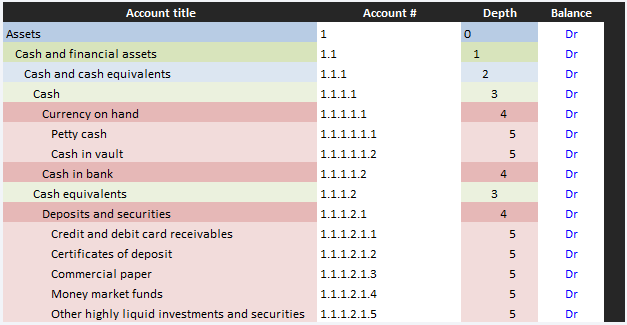

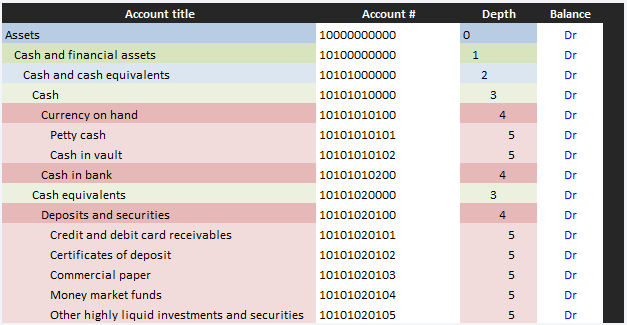

The COA uses a delimited account numbering scheme.

Since the traditional approach to COA construction has drawbacks, the COAs on this page use delimited account numbering (a.k.a. hierarchical coding), which makes the account structure flexible and infinitely expandable. As a bonus, it eliminates the need for superfluous sub-ledgers.

For example, the accounting software producer that publishes this page (link) has this to say: "The detail put into a chart of accounts sets the ceiling for financial analysis. If the chart of accounts doesn’t capture a data point, it won’t make it into any report" and "A well-structured chart of accounts also supports accurate, compliant financial statements. Misclassified accounts can distort key metrics and trigger audits, especially for businesses following Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP)."

So far so good.

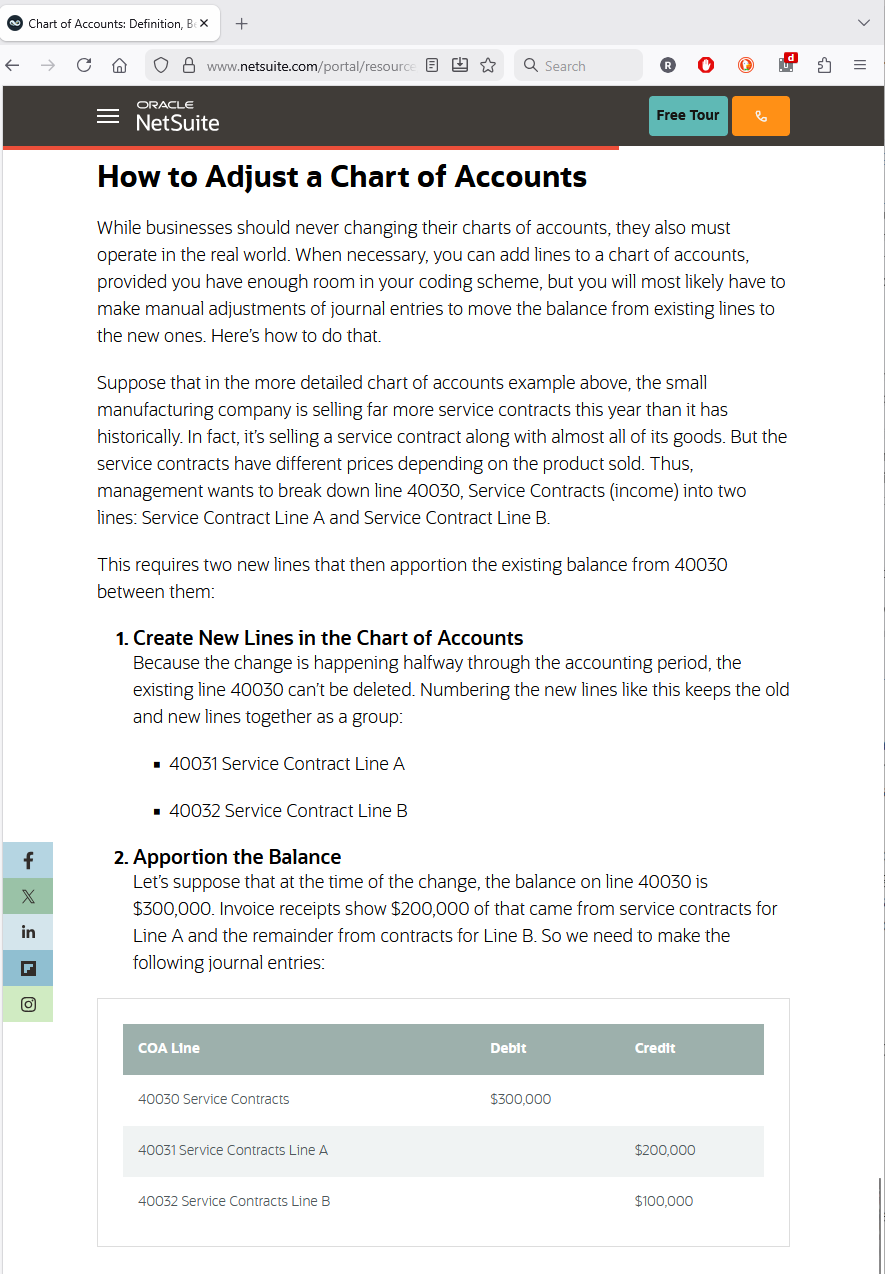

However, it then goes on to say: "A chart of accounts can become unnecessarily complex if it contains too many categories and subcategories" and recommends "If a chart of accounts has more than three levels, consider setting up subledgers."

The difficulty, allowing staff to add subledgers or items to subledgers on an ad hoc basis opens up a very wiggly can of worms and does nothing to address the fundamental issue which, as the page also correctly points out, happens when "Inconsistent naming and coding can cause staff to interpret accounts in different, unintended ways. This inconsistency creates reconciliation problems, reporting gaps, and trouble rolling up results across departments or entities."

Why vague COAs and ad hoc subledgers are so dangerous.

A frequently repeated recommendation is to keep the chart of accounts as simple and high-level as possible, and to “push detail” into subledgers or dimensions when needed. In theory, this keeps the general ledger tidy. In practice, especially in international groups, it often produces the opposite of what good accounting requires: inconsistency, inaccuracy, and loss of control.

The problem is structural. If the COA is overly general and staff are allowed to create subledgers ad hoc, the system as a whole becomes fragmented. Each accountant, department, or subsidiary can develop its own unofficial structure under the same top-level accounts. Over time, what appears to be a single, consistent account in group reporting actually represents a patchwork of different local practices and interpretations.

This is particularly acute in cross-border groups. Consider a US parent that gives its foreign subsidiary a rudimentary US GAAP reporting package with a handful of broad lines to fill out. The subsidiary completes the package to keep the parent satisfied, even when the mapping from local GAAP to those broad US GAAP categories is approximate at best. If local staff are also free to “solve” gaps by building their own subledgers and coding schemes, the risk is that the reported numbers look acceptable on the surface, but are structurally wrong underneath.

The less familiar local staff are with IFRS or US GAAP, the greater this risk becomes. Giving them wide latitude to modify the underlying structure through subledgers and custom codes is effectively delegating COA design to the people least equipped to do it. The very issues many experts warn about—“inconsistent naming and coding” causing reconciliation problems, reporting gaps, and trouble rolling up results across departments or entities—are made worse, not better, by vague COAs plus ungoverned subledgers.

A detailed, well-designed chart of accounts is the opposite of unnecessary complexity. It is a control instrument. By defining accounts precisely and structuring them carefully, the entity reduces the scope for arbitrary local interpretation, makes mappings from local GAAP to IFRS | US GAAP repeatable and auditable, and limits the need for improvised substructures that nobody fully understands. In this context, “detail” is not a problem to be hidden in subledgers; it is the means by which the entity protects itself against quiet, systemic misclassification in its financial reporting.

Why would a reputable software producer publish a page that seems this self-contradictory?

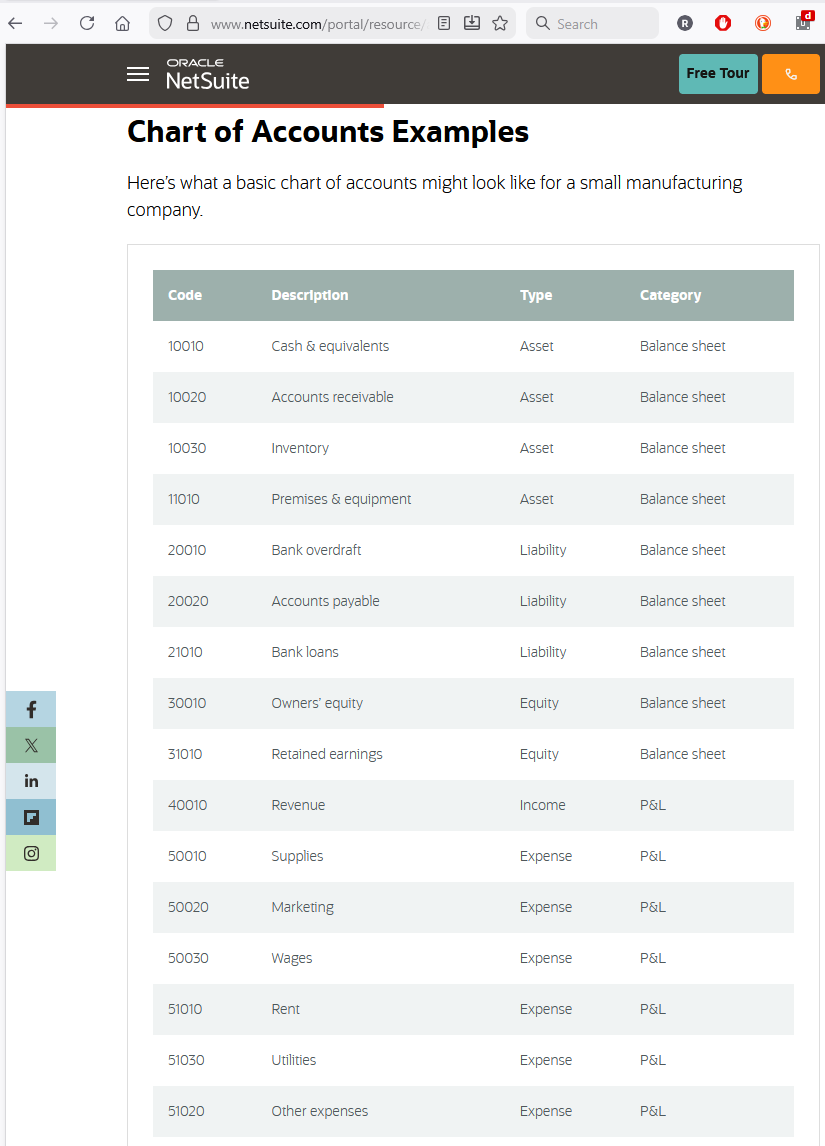

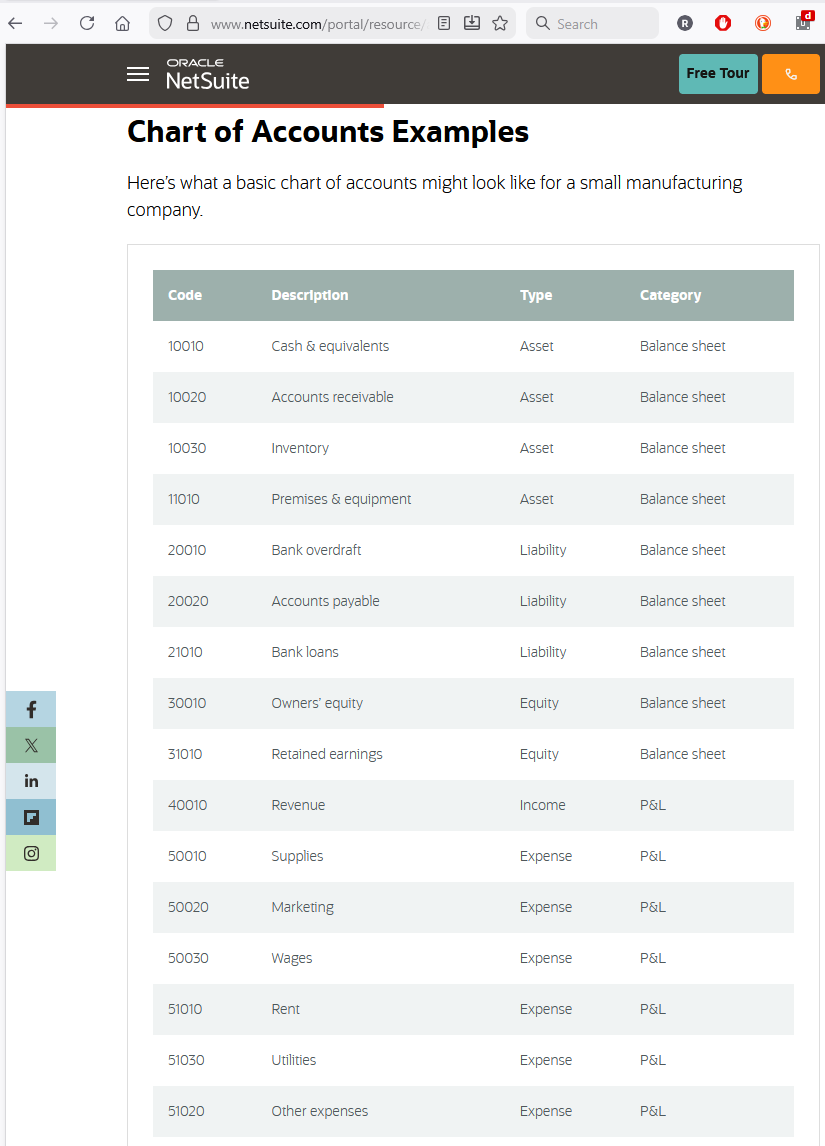

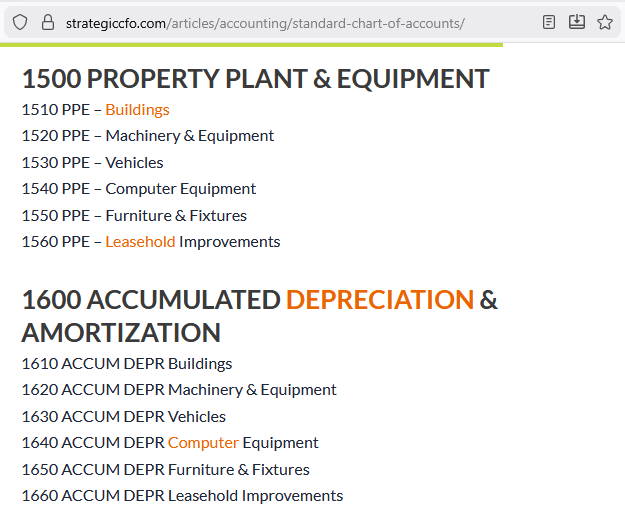

Perhaps because it assumed entities would use a traditional approach to account numbering it also illustrated.

Without any doubt, a numbering scheme such as this will make anything more than three levels practically unworkable. Also, as a bonus, it will likely cause chaos if even a small change is needed, particularly if more than 9 changes need to be made.

In some situations, no additional delimitation is necessary. For example, if the entity had cash on hand of 100,000 it would represent that balance as When it is necessary to identify a particular item recognized to an account a comma should be used. For example, assuming the entity had a bank balance at bank number 456 and bank number 567 it would If a particular item A particular item recognized to an account (

One would think, a such a software producer would have the resources to come up with a better solution than simply recommending sub-subledgers. Evidently not.

That said, accounting software, as any software, can be re-programmed to support a disciplined structure. The problem is not technical, but rather professional momentum and an unwillingness to break with tradition, not unlike the difficulty early humans likely had when someone suggested leaving the cave for a purpose-built house.

The traditional approach account numbering (block coding) has significant drawbacks. If done as suggested by some pages, it would limit the number of subordinated accounts to nine. While this can be overcome, this solution is far from optimal, practically guaranteeing that the result would only be readily readable to a machine while also making the changes humans must periodically make more difficult and prone to errors than necessary.

For example by defining two or more digit blocks:

Vague COAs requiring ad hoc subledgers may even be dangerous.

A frequently repeated recommendation (discussed above) is to keep the chart of accounts as simple and high-level as possible, and to “push detail” into subledgers or dimensions when needed. In theory, this keeps the general ledger tidy. In practice, especially in international groups, it often produces the opposite of what good accounting requires: inconsistency, inaccuracy, and loss of control.

The problem is structural. If the COA is overly general and staff are allowed to create subledgers ad hoc, the system as a whole becomes fragmented. Each accountant, department, or subsidiary can develop its own unofficial structure under the same top-level accounts. Over time, what appears to be a single, consistent account in group reporting actually represents a patchwork of different local practices and interpretations.

This is particularly acute in cross-border groups. Consider a US parent that gives its foreign subsidiary a rudimentary US GAAP reporting package with a handful of broad lines to fill out. The subsidiary completes the package to keep the parent satisfied, even when the mapping from local GAAP to those broad US GAAP categories is approximate at best. If local staff are also free to “solve” gaps by building their own subledgers and coding schemes, the risk is that the reported numbers look acceptable on the surface, but are structurally wrong underneath.

The less familiar local staff are with IFRS or US GAAP, the greater this risk becomes. Giving them wide latitude to modify the underlying structure through subledgers and custom codes is effectively delegating COA design to the people least equipped to do it. The very issues many experts warn about—“inconsistent naming and coding” causing reconciliation problems, reporting gaps, and trouble rolling up results across departments or entities—are made worse, not better, by vague COAs plus ungoverned subledgers.

A detailed, well-designed chart of accounts is the opposite of unnecessary complexity. It is a control instrument. By defining accounts precisely and structuring them carefully, the entity reduces the scope for arbitrary local interpretation, makes mappings from local GAAP to IFRS | US GAAP repeatable and auditable, and limits the need for improvised substructures that nobody fully understands. In this context, “detail” is not a problem to be hidden in subledgers; it is the means by which the entity protects itself against quiet, systemic misclassification in its financial reporting.

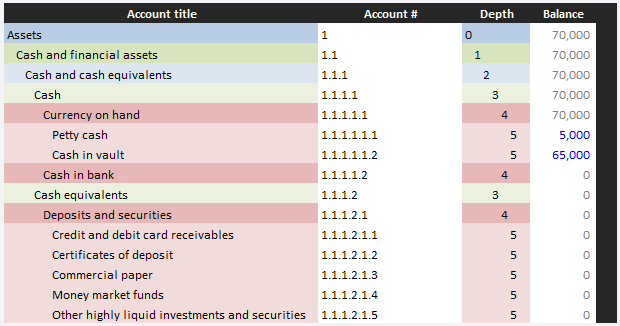

That being said, they do require some finesse to work as intended.

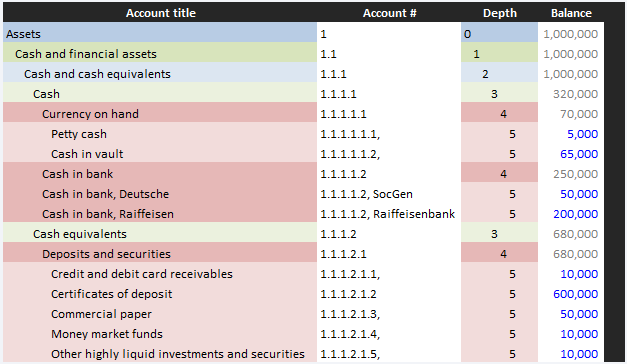

For example, if an entity had petty cash of 5,000 and cash in vault of 65,000 its COA could comprise:

By default, when a value is entered into an account at any particular depth, that account becomes a posting account and all higher level accounts summation accounts. However, this introduces some rigidity. To restore flexibility, a trailing comma may be added to explicitly denote posting accounts.

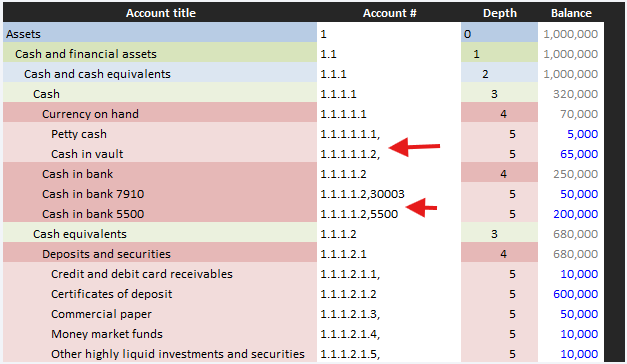

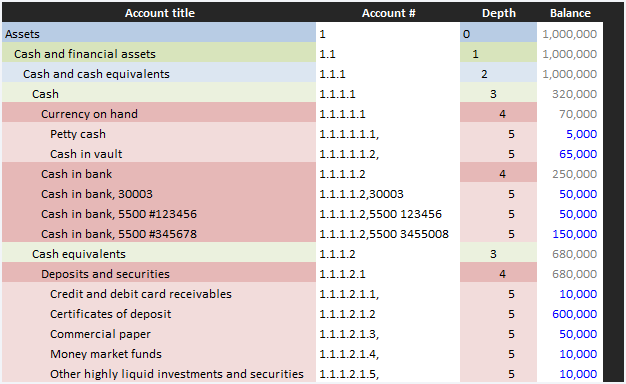

For example, in addition to petty cash and cash in vault, the entity could have two bank accounts as well as some cash equivalents. Instead of creating a sub-ledger to house the bank accounts, it could simply include them in the COA:

With a trailing comma, the account would be explicitly denoted as a posting account in that any information after the comma, such as bank number would be treated as metadata insofar as including it would be optional.

Since countries cannot agree on which language to speak (or even which side of the road to drive on) it is not surprising they cannot agree on a numbering convention.

In the English speaking world (the US, UK, Australia, etc.), it is 1,000,000.00 (although the "correct" side of the road still leads to drunken arguments).

In continental Europe, the right side of the road is universal, but Germany, Spain or Italy prefer numbering 1.000.000,00, while the French, Czechs and Slovaks are OK with both 1 000 000,00 and 1.000.000,00. Then, in Switzerland and Liechtenstein, not only may they buy bottles with removable caps, but they can even use apostrophes: 1’000’000.00.

Internationally, some countries do not even see the logic in groups of three. For example, in India they start that way but then go to 10,00,000.00.

Then comes the IT crowd. The consensus in that community is that grouping is for end users (who need to count using their fingers anyway), so 1000000.00 is perfectly fine (except in French or German IT where it's 1000000,00).

Not that Windows, de-facto arbiter of all things informational, is much help. Since it demands you set one single region, once you do, it assumes no other regions exist. So, if one happens to need to process files from all over the world, one has to make certain their Excel is reading the data correctly.

Note: fortunately, an Excel mix-up is unlikely to make a spaceship crash and burn, like once happened when scientists mixed up Metric and Imperial on a trip to Mars.

In any event, as far as this page is concerned, subscribers may select whatever delimitation they like.

If they would rather delimit accounts with a comma instead of a decimal point, switching is as easy as search and replace (just do not forget to, for example, first switch . to .. then , to . and finally .. to , otherwise it will make a mess).

Also note: to be fair, in Excel one can always go to File > Options > Advanced and uncheck 'Use system separators' even though the power user would rather pass since, as someone wise on YouTube once said, "Ain't nobody got time for that."

In some jurisdictions, banks are assigned relatively short numeric codes, for example France (5‑digit) or the Czech Republic (4‑digit), making it convenient to refer to the bank by its number.

In other jurisdictions, for example Germany (8‑digit) and the US (9‑digit), they are assigned relatively long numbers, so using the bank's name or an abbreviation is more convenient.

As such, it may be numeric, alphabetical or alphanumeric. For example:

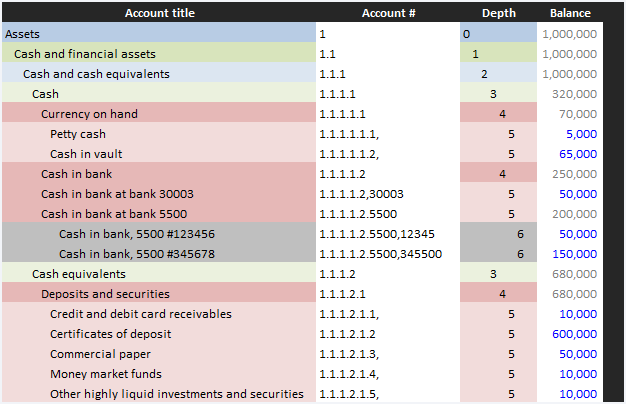

If instead of two banks each with a single account, one bank had two accounts:

Important: however, if for some reason a summation of the accounts at 5500 were needed, a new level should be added. Account 1.1.1.1.2 would thus be a sum of accounts 1.1.1.1.2,7910, 1.1.1.1.2.5500,12345 and 1.1.1.1.2.5500,345500 so 1.1.1.1.2.5500 (a summation account) would not be included in the higher level summation.

Note: since account numbers do not necessarily need to be sequential, account number 1.1.1.1.2.5500 does not need to be 1.1.1.1.2.1. The only convention to be followed: any value preceding the trailing comma is numeric and unique.

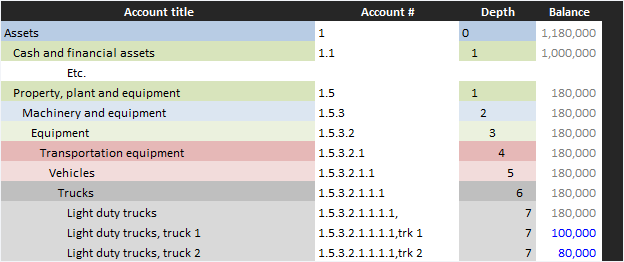

The same general approach would be used throughout the COA.

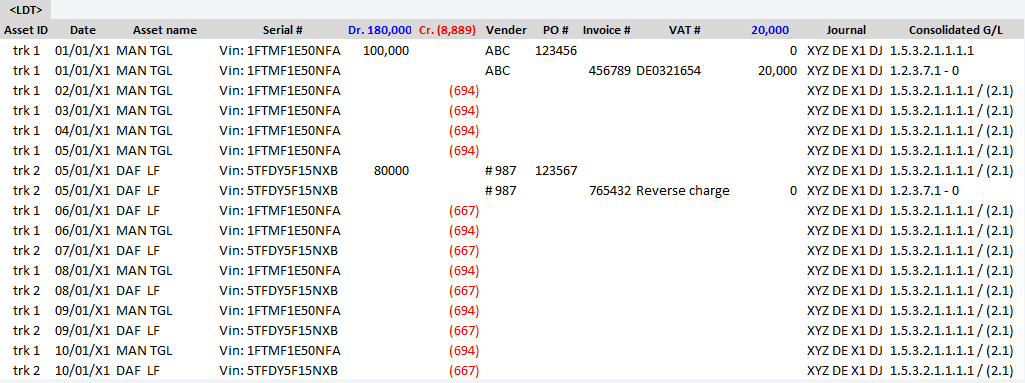

However, when an account comprises multiple items, adding each to the COA would be untenable. For example, if XYZ had two light duty trucks (a MAN-TGL that had cost 100,000, a.k.a. truck 1, and a DAF-LF that had cost 80,000, a.k.a. truck 2), this approach would be unworkable:

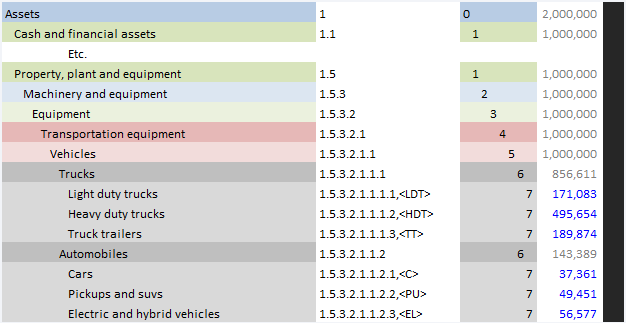

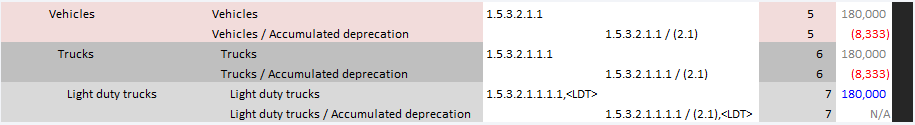

Instead, a sub-ledger, e.g. <LDT> (comprising all light duty trucks) should be associated with the Light duty trucks COA account:

Other classes of items, e.g. heavy duty trucks, pickups, etc., would each occupy their own sub-ledger and be incorporated thusly:

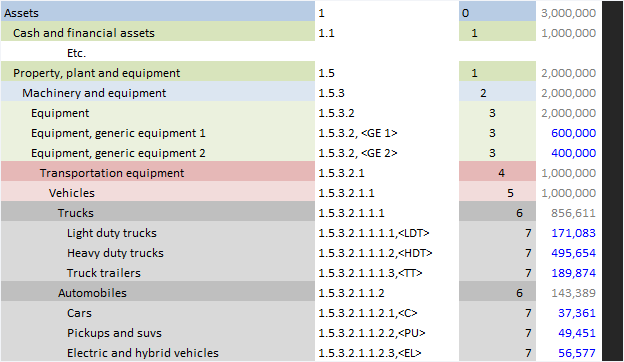

It is also possible the entity would not need the COA's full depth. In this case, it could simply add additional items (such as generic, undifferentiated equipment) at a higher depth. For example:

It is also possible the entity would need to keep the adjustment separate at the COA level (for example to make mapping the COA to the financial report more workable). In this situation, it would use the Expanded COA instead of the Advanced COA:

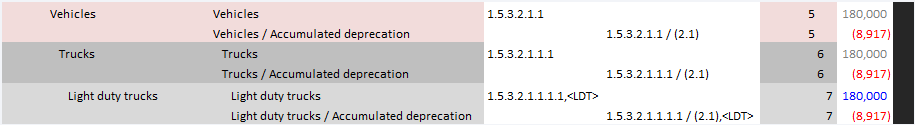

If the entity elected to depreciate assets at the class rather than individual asset level, it could simply add the adjustment to the class account for example:

Note: the depreciation / accumulated depreciation calculation in the first illustration assumes the DEF had a useful life of 10 years while the MAN's was 12 years. For the second illustration, a class depreciation of 12 years was used for both. The same method (straight-line) and salvage value (zero) was used in both illustrations.

The COAs do not make a current/non-current distinction (usually).

As an item's status as either current or non-current is a reporting and disclosure issue, not a recognition issue. For example, a receivable due in 90 days represents a claim to cash just as a receivable due in 730 days. Nevertheless, from an accounting guidance perspective, while a receivable is a receivable, a receivable with a long payment term also provides debtor financing, which the creditor must account for. Specifically, both IFRS and US GAAP require all receivables with a term of more than one year to be discounted and measured at present value.

Technically, as outlined in IFRS 15.62 | ASC 606-10-32-17, not every contract with a customer results in a claim to cash with a significant financing component that would require discounting. However a receivable (IFRS 15.106 | ASC 606-10-45-2: a right to an amount of consideration that is unconditional) would always require discounting unless the entity chooses to apply the practical expedient outlined in IFRS 15.63 | ASC 606-10-32-18.

Thus, the question is not whether an item's current/non-current status should be reported, but whether it should be given accounting recognition at the account level.

Both options are technically feasible. However, one introduces additional complexity and may even involve unnecessary effort. For example, in a current/non-current chart of accounts, a receivable with a 730-day term would be non-current. Then, when its term dipped below 365, it would be current and would need to be reclassified.

However, non-current receivables are measured at present value from inception to derecognition. Thus, when reclassified, the original 730-day receivable would have a different measurement basis than the other 30, 60, or 90-day receivables in the same account, even though they all now represent identical, unconditional claims to cash. Messy.

Obviously, nothing would prevent an entity from not applying the practical expedient and discounting all receivables. However, in practice, discounting is practically always reserved for receivables with terms extending past one year.

This begs the question: why have two separate accounts when a receivable is always a receivable, and its current/non-current status only influences its measurement?

The practical solution, a single natural account (receivables) on which all unconditional claims to cash would be recognized. To this account two attributes (a measurement attribute and a reporting/disclosure attribute) would be added. Not only is the solution simple and elegant, but it allows the item to remain on the original account untouched until derecognition.

Nevertheless, some accountants insist on a current/non-current COA (for valid reasons).

The Counterpoint

While a single-account, attribute driven solution can be considered "simple and elegant," many accountants stick to separate accounts for a few practical reasons:

- System limitations: not every ERP handles dimensions well. Many mid-range accounting systems generate financial statements directly from the COA structure. If it is not in a separate account, the software cannot "see" it as non-current.

- Trial balance clarity: a Trial balance is the "truth" for many auditors. If they see ¤100,000 in one account, they would need to dig into a sub-ledger to see that ¤50,000 of that is non-current. Separate accounts provide that visibility at a glance.

- The discounting reality: while the claim to cash is unconditional, the time value of money \( PV = \sum_{t=1}^{n} \frac{CF_t}{(1+1)^t} \) means that a claim to cash today is not a claim to cash in two years. From a reporting perspective, they are not comparable assets until that time gap closes.

As a dimensional COA will lead to the correct amount being reported in either case, this is a moot point.

Neverthless, some practitioners prefer to see PV clearly reflected in the G/L and TB, not just on the BS.

Since it is not our place to dictate judgment, in addition to the unclassified COAs, we also provide COAs that do make the current/non-current distinction.

The COA includes both nature and function of expense accounts.

From an accounting perspective, a nature of expense classification scheme is more practical.

Employee benefits are a good example.

Assume a very simple company with three employees (one in production, one in sales and one in administration) which it compensates in three ways: hourly wage, salary plus commission and monthly salary. Associated with these costs, it also incurs: social security and health insurance.

As each cost has a different measurement basis, it would be reasonable to use three direct payroll accounts : Wages 5.1.2.1.1.1 (hourly measurement), Salaries 5.1.2.1.1.2 (monthly measurement), Commissions 5.1.2.1.1.3 (measured by sales amount), and two indirect accounts: Social Security 5.1.2.1.4.1 and Health Insurance 5.1.2.1.4.2 (whose measurement is derived from the direct compensation amounts).

If the company decided to structure its accounts by function instead, it would need:

In Cost of Sales: Wages 5.2.1.1.2.2.1, Social Security 5.2.1.1.2.2.2 and Health Insurance 5.2.1.1.2.2.3.

In Selling Expenses: Sales Salaries 5.2.2.1.1.1.1.1, Sales Commissions 5.2.2.1.1.1.1.2, Social Security 5.2.2.1.1.1.1.3 and Health Insurance 5.2.2.1.1.1.1.4

In General and Administrative Expenses: Salaries 5.2.2.2.1.1.1.1, Social Security 5.2.2.2.1.1.1.2 and Health Insurance 5.2.2.2.1.1.1.3.

The better approach is thus to use nature of expense accounts for day-to-day recognition and measurement, in that these would be mapped to the function accounts for disclosure at the end of each period.

Assume the entity recognized period direct compensation costs of currency unit 1,000,000. In addition, it incurred social security tax and health insurance costs at rates of 30% and 10% respectively (for simplicity, also assume that production wages are expensed as incurred rather than being capitalized to inventory).

At the end of the accounting period the balances on the emplyee benefit (nature of expense) accounts were:

Wages 5.1.2.1.1.1: 400,000

Salaries 5.1.2.1.1.2: 400,000

Commissions 5.1.2.1.1.3: 200,000

Social Security Tax 5.1.2.1.4.1: 300,000

Health Insurance 5.1.2.1.4.2: 100,000

XYZ next determined that its production workers spent 90% of their time on production and 10% on repairs and maintenance, in that 40% of that maintenance was performed on delivery equipment. the entity also determined that 25% salaries were paid to sales staff with the remainder paid to administrative workers, split 60%/40% between office staff and officers.

To prepare its (function of expense) financial report it allocated:

Wages 5.1.2.1.1.1 to accounts: Cost Of Sales/Direct Labor 5.2.1.1.2.2: 384,000 and Selling/Repairs And maintenance 5.2.2.1.3.3 CU16,000

Salaries 5.1.2.1.1.2 to accounts: Selling/Sales Staff Compensation: 5.2.2.1.1.1.1: 100,000, General And Administrative/Office Staff Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.1: 180,000.00 and General And Administrative/Officer Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.2: 120,000

Commissions 5.1.2.1.1.3 to account Selling/Sales Staff Compensation: 5.2.2.1.1.1.1: 200,000

Social Security Tax 5.1.2.1.4.1 to accounts: Cost Of Sales/Direct Labor 5.2.1.1.2.2: 115,200, Selling/Repairs And maintenance 5.2.2.1.3.3 CU4,800, Selling/Sales Staff Compensation: 90,000, General And Administrative/Office Staff Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.1: 54,000, and General And Administrative/Officer Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.2: 36,000

Health Insurance 5.1.2.1.4.2 to accounts: Cost Of Sales/Direct Labor 5.2.1.1.2.2: 38,400, Selling/Repairs And maintenance 5.2.2.1.3.3 CU1,600, Selling/Sales Staff Compensation: 30,000, General And Administrative/Office Staff Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.1: 18,000, and General And Administrative/Officer Compensation 5.2.2.2.1.1.2: 12,000

Besides a simpler account structure, this approach also allows individual expense to be recognized, day-to-day, by relatively inexperienced staff, while the period end allocations can be performed (supervised) by personnel well versed in the nuances of IFRS and US GAAP guidance

Similarly, as many national GAAPs prefer or prescribe nature of expense recognition, this approach works well at local subsidiaries of (especially) US based companies, that the day-to-day accounting can be performed by local staff (accountants trained in the local GAAP), while the period end adjustments can be performed by reporting specialists (staff trained in US GAAP and/or IFRS).

Obviously, since knowledgeable does not necessarily require presence, the local accounting staff can perform their tasks locally, while the reporting specialists can perform their tasks in close proximity to the management responsible for the final reports.

From a reporting perspective, a function of expense scheme yields better results.

Providing the minimum possible information, ABC and XYZ published function of expense P&Ls:

|

|

ABC |

XYZ |

|

Revenue |

100 |

100 |

|

Cost of sales |

60 |

40 |

|

Gross profit |

40 |

60 |

|

Administrative expenses |

30 |

50 |

|

Net income |

10 |

10 |

Again providing the minimum possible information, ABC and XYZ published nature of expense P&Ls:

|

|

ABC |

XYZ |

Revenue |

100 |

100 |

Material |

10 |

10 |

|

50 |

50 |

|

Services |

10 |

10 |

Depreciation |

20 |

20 |

Net income |

10 |

10 |

In a nature of expense P&L, production and administrative employee benefits are not distinguished from one another.

Of the two formats, which would allow financial statement users to better assess the entity's operating efficiently?

Note: this issue is explored in more death in the overall section of this page.

A combined approach leads to the best results.

To reflect that both nature and function of expense reporting have merits, ASU 2024-03 (ASC 220-40-50-6) updated US GAAP disclosure guidance to require entities to disclose nature of expense items in the footnotes.

From an accounting perspective, this makes a chart of accounts that captures both nature and function of expense information necessary for compliance with both US GAAP and IFRS.

Technically, IFRS 18 always requires key information by nature of expense. Presenting operating expenses by function (as under IAS 1) remains optional, even though practically all IFRS reporters do present expenses by function in their financial statements.

Note: while it would be possible to create a COA that treated either function or nature as accounts with the other treated as attributes, presenting them as separate account classes is a more practical solution.

The COAs define accounts as well as accounts with attributes.

The traditional approach to items such as accumulated depreciation as illustrated here was to record them in separate contra‑accounts. While that was practical when ledgers were maintained manually, technology has moved on.

Note: PP&E is depreciated not, as suggested above, amortized.

In a relational, dimension‑driven accounting system, item attributes such as depreciation, amortisation, accumulated impairment, currency, current/non‑current status, accumulated fair value adjustments and whether changes flow through profit or loss or other comprehensive income can be stored as attributes of the underlying item rather than as separate accounts. Treating these attributes as dimensions simplifies the chart of accounts, sometimes a bit, sometimes a lot.

The COA assists with XBRL mapping.

The SEC requires financial statements filed with it to be tagged using Inline XBRL. While many other regulators do not yet require IFRS financial statements to be XBRL‑tagged, machine‑readable reporting formats are becoming increasingly common.

XBRL taxonomies are designed for reporting, not for day‑to‑day bookkeeping, so their structure is not suitable as a chart of accounts. Nevertheless, to make drafting XBRL‑tagged reports as straightforward as possible, each extended chart of accounts on this page is also provided in a version that includes appropriate XBRL cross‑references.

Important

As XBRL taxonomies do not serve the same purpose as a chart of accounts, a one‑to‑one, line‑by‑line mapping between a COA and an XBRL taxonomy is not possible. XBRL tagging will always require judgment at report level and any XBRL report prepared using these COAs should be validated using appropriate XBRL validation tools.

The comment section for each COA includes links to online validation resources.

The COA is updated regularly.

The COAs on this page are updated annually to reflect the changes the IASB and FASB make to their XBRL taxonomies.

The updates may also include targeted improvements to the COA's structure.

If you would like to suggest an improvement, please contact me here.

The COA can be updated regularly.

Using a flexible account hierarchy and numbering scheme (above) makes it possible to regularly update the COA while keeping its overall structure intact.

In a parent/subsidiary environment, an optimal approach is to designate a particular depth as corporate, while allowing subsidiaries to make autonomous changes below that depth. For example, a subsidiary that did not own any trucks would not need a Trucks # 1.5.3.2.1.1.1 account. It may, however, find use for:

One aisle passenger aircraft # 1.5.3.2.1.4.1.1

Two aisle passenger aircraft # 1.5.3.2.1.4.1.2

Large passenger aircraft # 1.5.3.2.1.4.1.3

Or perhaps:

A320 / 737 # 1.5.3.2.1.4.1.1

A330 / 777 # 1.5.3.2.1.4.1.2

A380 / 747 # 1.5.3.2.1.4.1.3

If the subsidiary later began offering executive air transportation, it could add VIP or business passenger aircraft # 1.5.3.2.1.4.1.4 or perhaps A318 / 757 # 1.5.3.2.1.4.1.4 to the list.

If the structure is robust and logical, the subsidiary could even be allowed to make this change autonomously without central approval. On the other hand, if more central control is needed, a sufficiently robust and logical structure could allow approval to be granted (or denied) not in days or weeks but minutes or hours.

As a bonus, a robust and logical account structure minimizes the need for the ad hoc sub-ledgers that plague many organizations without a robust and logical account structure.

Why vague COAs and ad hoc subledgers are so dangerous.

A frequently repeated recommendation is to keep the chart of accounts as simple and high-level as possible, and to “push detail” into subledgers or dimensions when needed. In theory, this keeps the general ledger tidy. In practice, especially in international groups, it often produces the opposite of what good accounting requires: inconsistency, inaccuracy, and loss of control.

The problem is structural. If the COA is overly general and staff are allowed to create subledgers ad hoc, the system as a whole becomes fragmented. Each accountant, department, or subsidiary can develop its own unofficial structure under the same top-level accounts. Over time, what appears to be a single, consistent account in group reporting actually represents a patchwork of different local practices and interpretations.

This is particularly acute in cross-border groups. Consider a US parent that gives its foreign subsidiary a rudimentary US GAAP reporting package with a handful of broad lines to fill out. The subsidiary completes the package to keep the parent satisfied, even when the mapping from local GAAP to those broad US GAAP categories is approximate at best. If local staff are also free to “solve” gaps by building their own subledgers and coding schemes, the risk is that the reported numbers look acceptable on the surface, but are structurally wrong underneath.

The less familiar local staff are with IFRS or US GAAP, the greater this risk becomes. Giving them wide latitude to modify the underlying structure through subledgers and custom codes is effectively delegating COA design to the people least equipped to do it. The very issues many experts warn about—“inconsistent naming and coding” causing reconciliation problems, reporting gaps, and trouble rolling up results across departments or entities—are made worse, not better, by vague COAs plus ungoverned subledgers.

A detailed, well-designed chart of accounts is the opposite of unnecessary complexity. It is a control instrument. By defining accounts precisely and structuring them carefully, the entity reduces the scope for arbitrary local interpretation, makes mappings from local GAAP to IFRS | US GAAP repeatable and auditable, and limits the need for improvised substructures that nobody fully understands. In this context, “detail” is not a problem to be hidden in subledgers; it is the means by which the entity protects itself against quiet, systemic misclassification in its financial reporting.